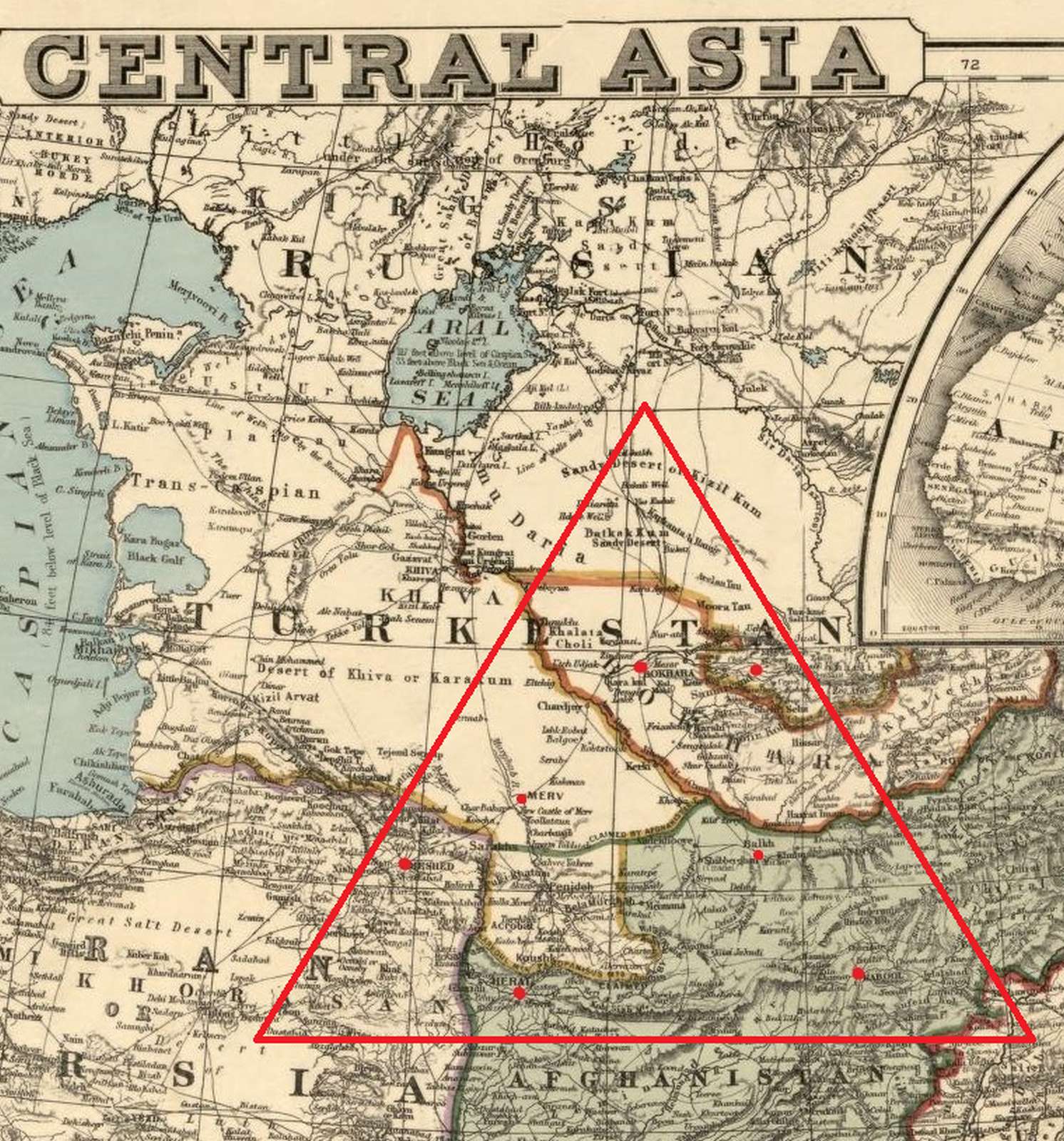

Afghanistan, Central Asia, Iran – “The Jewish triangle”

The Persian-speaking Jewish communities wedged between Afghanistan, Iran, and the former Soviet republics of Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan have received very little scholarly attention. Even in the modern period, we face significant gaps in the Jewish historical narrative and blank spots on the Jewish map of Afghanistan, Central Asia, and Iran.

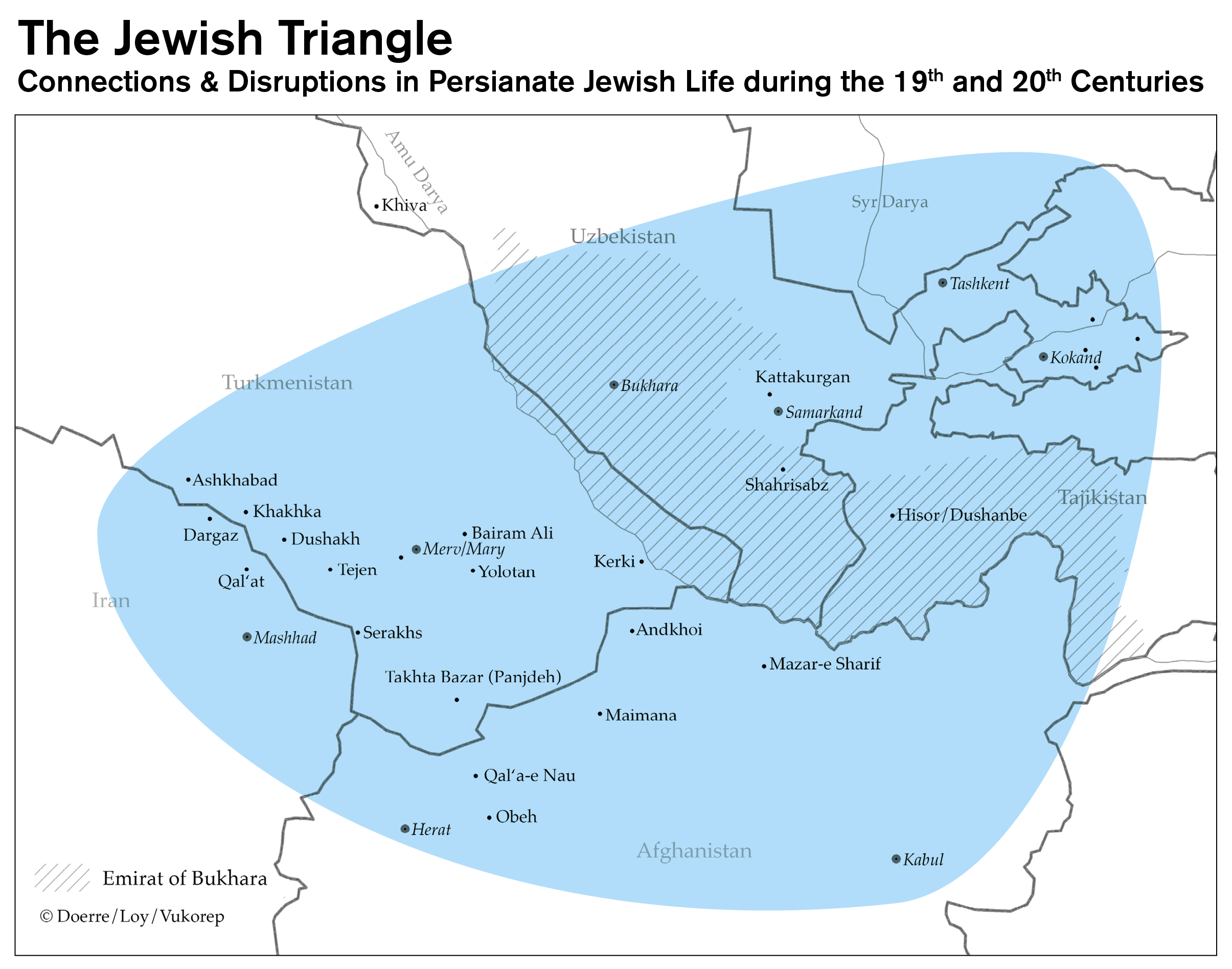

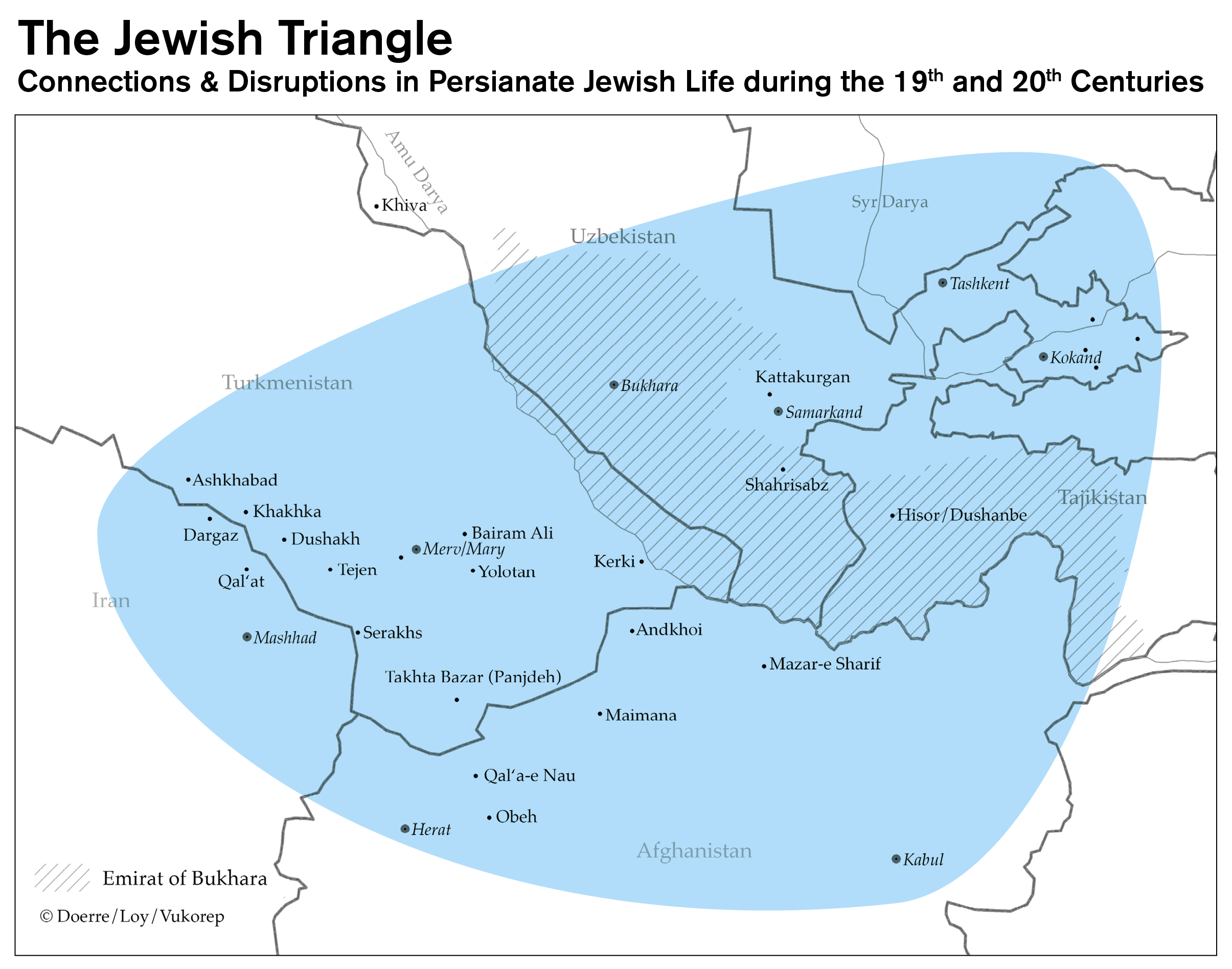

For centuries, the Jews of Central Asia were part of a broader Persianate world that thrived along the Silk Roads. This region was divided into three major states: the Safavid, the Mughal, and the Uzbek empires. In the 18th and 19th centuries, Persian-speaking Jewish communities became part of (Qajar) Iran, (Durrani) Afghanistan, the Bukharan Emirate, and (Russian) Turkestan. Islamic historiography and mapping refer to this eastern heartland of the medieval Muslim world, with its urban centers such as Mashhad, Herat, Balkh, Merv, Bukhara, and Samarkand, as Khurasan (“the land of the rising sun”). Jews sometimes referred to this vast area as the “Jewish Triangle.”

The end of the Jewish Triangle is closely linked to the restrictive policies of the Soviet Union and Afghanistan’s nationalization efforts in the early 1930s. These measures aimed to bring the trade of essential goods under state control, which deprived Jews in Afghanistan of the very basis of their livelihood. Consequently, the political and economic strategies of Afghanistan and the Soviet Union effectively dislocated the traditional Jewish commercial and cultural networks in the border region between Afghanistan, Iran, and Soviet Central Asia and dismantled what was once the Jewish Triangle.

After the founding of the state of Israel, most Jews emigrated from Afghanistan. The last families left Kabul in the early 1980s. The remaining Jews of Mashhad, who had kept their faith in secret, also left Iran between the 1940s and the 1980s. The borders of the Soviet Union remained closed. Only in the 1970s the Soviet government allow Jewish citizens to leave. Within a decade, around 250,000 Soviet Jews had emigrated, primarily to Israel and the United States, among them many Bukharan Jews. However, in the early-1980s, Moscow stopped the first wave of legal Jewish emigration from the Soviet Union. The mass exodus from Central Asia took place after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Today, there are no Jews left in Mashhad, in Afghanistan, or in most towns of former Soviet Central Asia. Most live in Israel and the United States of America.

The Project

We argue that this historical-geographical framework is still helpful in understanding and describing the history of the Persian-speaking Jewish communities in the early 20th century. So far, the history and historiography of these groups have been divided according to the borders of modern nation-states. In the literature, we read about the Jews of Iran, the Jews of Afghanistan, and the so-called Bukharan Jews—that is, those Central Asian Jews who came under Russian rule in the late nineteenth century, followed by Soviet rule from the 1920s.

These modern narratives suggest the existence of culturally homogenous and isolated communities, neglecting their broad cultural and linguistic commonalities and overlapping family biographies. Colonial, Soviet, and post-Soviet perspectives on and narratives of the region and its population, as well as a Eurocentric and Israel-centred Diaspora approach, have contributed heavily to these misunderstandings. These limited narratives also fed back into an exclusive self-consciousness of the respective Jewish groups, who developed their own distinct “national” group identities only after leaving their home countries in the twentieth century.

The framework of modern nation-states is insufficient to fully capture the diverse past and present of Persian-speaking Jewish communities, which have unique local experiences and intertwined histories. We argue that the spatial concept of the “Jewish Triangle”—comprising its key cities, Bukhara, Samarkand, Tashkent, Herat, Mashhad, and many others—up to the 1930s provides a more effective framework for understanding the connections between these communities and their Muslim neighbors. To illustrate the links, disruptions, and mobility within Jewish life in the regions of Afghanistan, Central Asia, and Iran, we follow and examine several family histories that span the entire area.

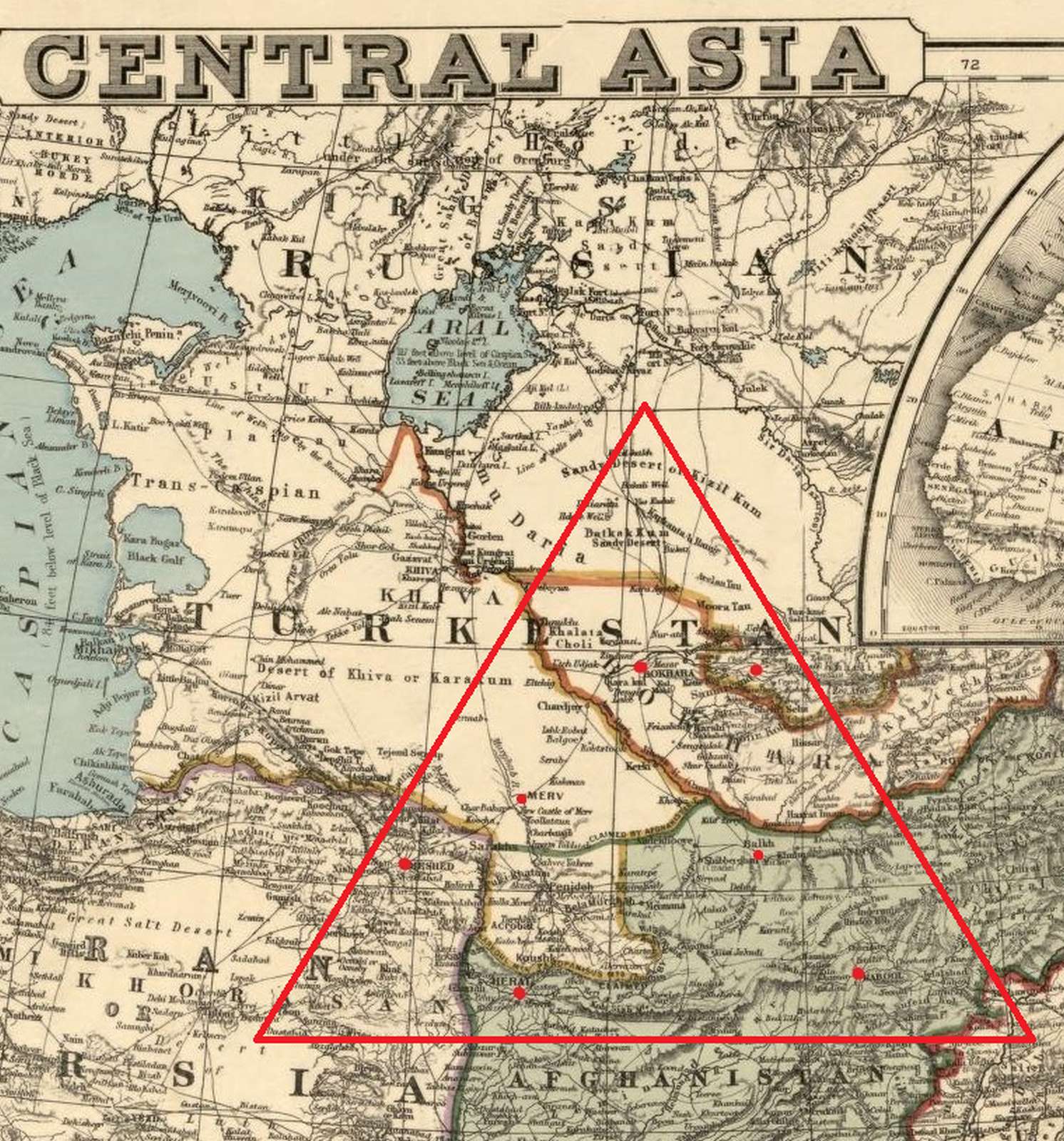

G.W. & C.B. Colton & Co. Central Asia: Afghanistan and her relation to British and Russian territories. New York: G.W. & C.B. Colton & Co, 1885. Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/2004629038/. Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division (detail edited). When the map was published (in 1885) major Jewish communities (marked in red) were located in the Emirate of Afghanistan (Herat, Balkh, Kabul), the Emirate of Bukhara (Bukhara), Iran (Mashhad), and Russian Turkestan (Merv, Samarkand, Tashkent). Not on the map is the Ferghan valley (Kokand, Marghilan, Skobeleff, Andijan).

Places and Spaces

At the same time, we will also stress the importance of locality. The Jews of Afghanistan, Central Asia, and Iran spoke local varieties of Persian, which they wrote in the Hebrew script—so-called Judeo-Persian. Texts written in Judeo-Persian have been documented as far back as the 8th century, making them the oldest preserved written documents in New Persian. Like the Persian spoken by Muslims, the Judeo-Persian varieties of the “Jewish Triangle” varied from region to region and town to town. Depending on their place of residence, Persian-speaking Jews also differed in clothing, cuisine, and other cultural features, such as customs, art, and music. Deeply influenced by their Muslim cultural environment, they shared much of their Muslim neighbors’ culture, traditions, and tastes, including their language and literature.

A significant shift in population within the “Jewish triangle” began in 1839, when in Mashhad (in northeastern Iran), a group of Muslims attacked the town’s Jewish quarter and set fire to the synagogue. To prevent further escalation of violence against the Jews, Islamic religious leaders intervened and promised the rioters that the entire Jewish community of Mashhad would convert to Islam. With this forced conversion, the Jewish community of Mashhad officially ceased to exist, and the converts became known as “New Muslims” (Jadid al-Islam). Many of these converts became Muslims outwardly but maintained their Jewish faith and observed their religious laws and ceremonies at home and in secret. Others opted for emigration and moved towards neighboring Herat and other cities in northern Afghanistan and Central Asia. In Herat, these refugees became the dominant element in the Jewish community and turned the community there into the largest Jewish community in Afghanistan. Among Persian-speaking Jewish communities, the Jews of Afghanistan remain the least studied and least known.

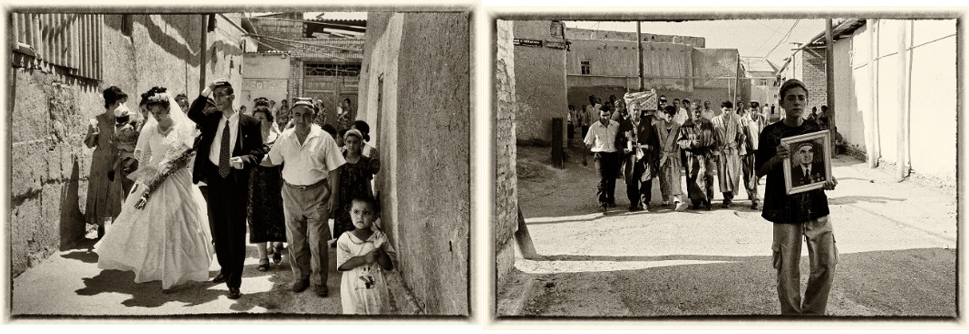

Scenes from Jewish Life in Central Asia. Collection of the Bukharan Jewish Museum, New York, 2025.

Connections and Disruptions

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, Jews considered Herat, Mashhad, and Bukhara sister cities. Merchants were active within the Jewish Triangle, maintaining connections between its major cities and surrounding towns with Jewish populations. Cross-border and inter-city marriages were quite common. Jews even founded new communities when the political and economic circumstances seemed favorable and more suitable for them being Jewish. The Russian conquest of Central Asia and the economic boom supported by the region’s connection to the Empire’s railroad network also brought new opportunities for Jews. The communities in Merv, Samarkand, and the Ferghana Valley grew considerably. Until the Russian Revolution, Jewish merchants and entrepreneurs were highly successful, with some families belonging to the richest classes in the Empire.

However, some Jews who had left the Triangle before the arrival of the Bolsheviks radically changed the political landscape. In the 1880s, Jews from Central Asia purchased land and established a colony outside the walls of the Old City of Jerusalem. This new settlement quickly became the main center of book production for the Persianate Jews. Before the First World War, there was a lively exchange of people, goods, and ideas between the “Bukharan neighborhood” (Shekhunat ha-Bukharim) in Ottoman Palestine, Central Asia, Afghanistan, and Iran.

The end of the European Empires also heavily affected the lives of Persianate Jews. Connections between Central Asia and Palestine were cut. The community in Jerusalem suffered bitterly. In Central Asia, the Bolshevik takeover was a catastrophe for the wealthy class of Jewish merchants and entrepreneurs. The Emirate of Bukhara was dissolved, and in 1924, the map of Central Asia was redrawn according to Stalin’s ideas of nation and nationality. For the next decade, a secular culture of the “national minority” of so-called native Jews was forged and supported by the Soviet state. At the same time, religious leaders were persecuted, and private entrepreneurship was banned. By the mid-1930s, when the southern borders with Afghanistan and Iran were finally sealed, about one-tenth of the “native Jews” had fled from Soviet Central Asia. This “Bukharan Jewish refugee crisis” (Sara Koplik) also led to the expulsion of the native Jewish population of northern Afghanistan and the end of the Jewish Triangle.

The three-year bilateral research Project “The Jewish Triangle: Connections and Disruotions in the Persianate Jewish Life during the 19th and 20th Centuries” was launched in July 2023 by Dr. Thomas Loy (Oriental Institute of the Czech Academy of Sciences) and Dr. Ariane Sadjed (Institute of Iranian Studies of the Austrian Academy of Sciences). The project is funded by GAČR (23-08007K) and the Austrian FWF. Dr. Ahmad Azizy joined the project as a postdoc in August 2024 and focuses on the history of Jews in Afghanistan.

What we do/have done so far

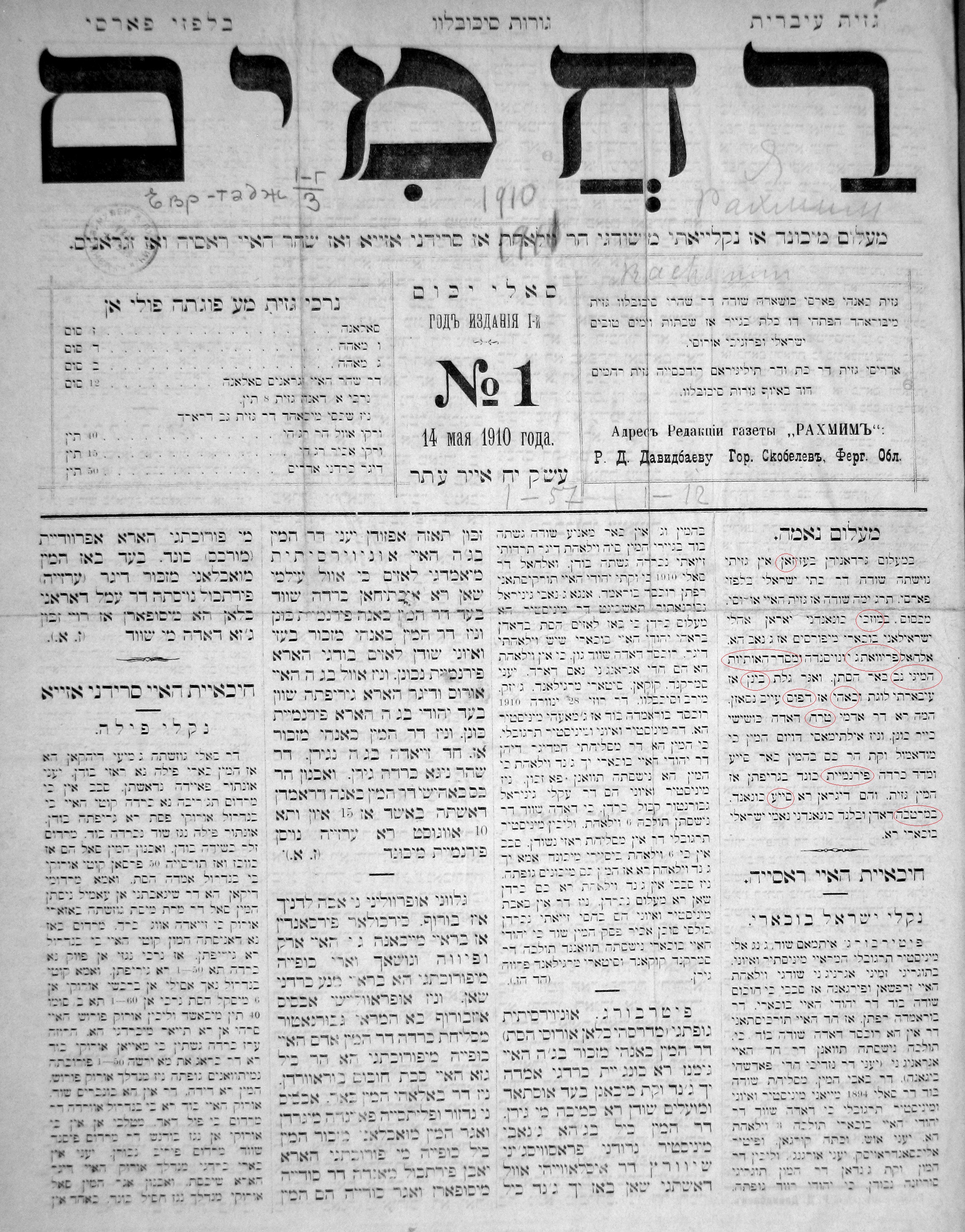

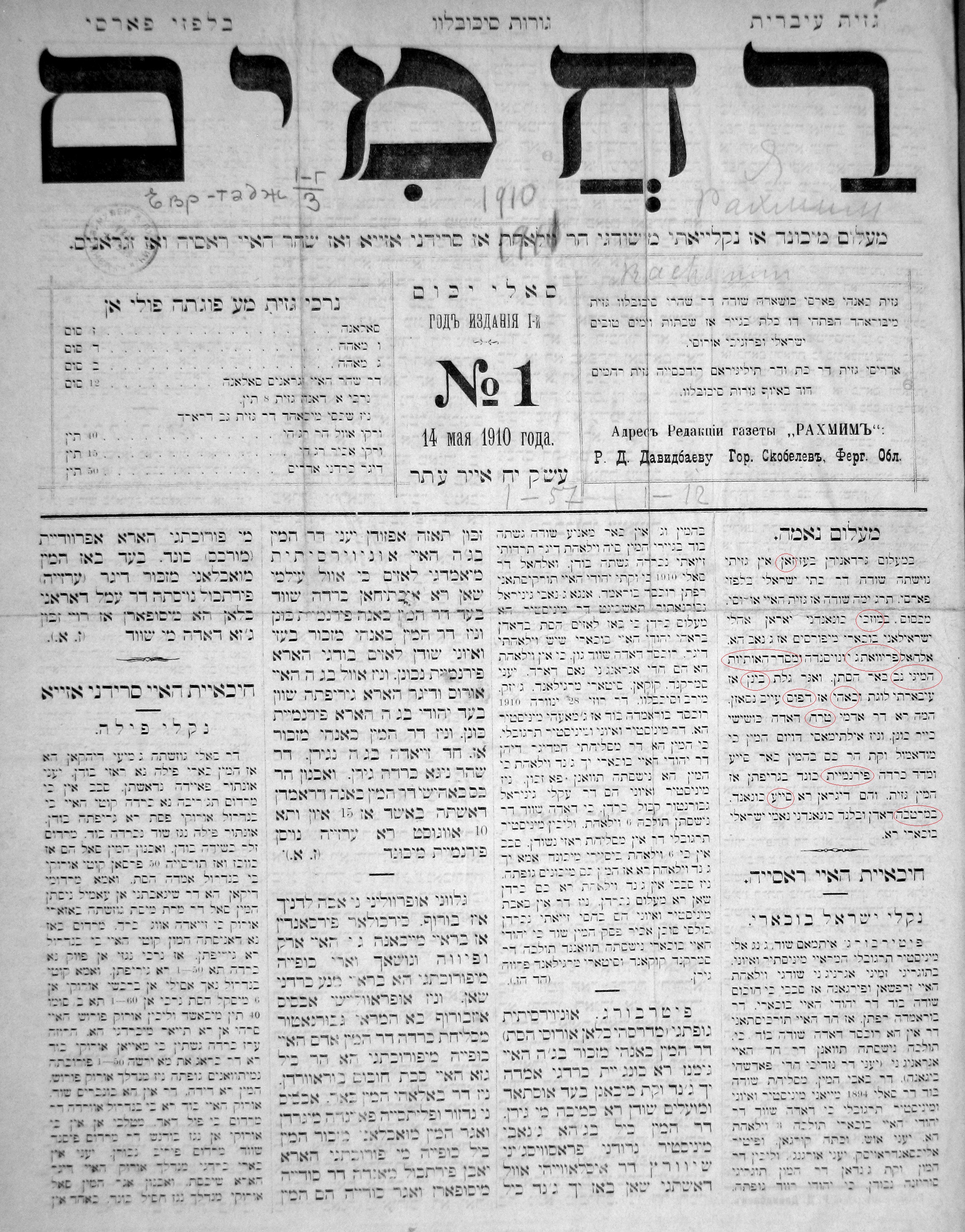

Reading and analysing the collection of the Judeo-Persian newspaper/periodical Rakhamim (Mercy), which was published from 1910 to 1914 in Russian Turkestan (today’s Uzbekistan), first in Skobeleff (today’s Far’gona) and later in Kokand.

Rakhamim (Mercy), title page, issue 1, May 1910

Rakhamim (Mercy), title page, issue 1, May 1910

A total of 306 issues of Rakhamim are available on the website of the Israeli National Library; https://www.nli.org.il/en/newspapers/rahamim/.

Reading and analysing materials related to the Jewish Triangle kept in the Wiener Holocaust Library (London).

Searching for, reading, and analyzing materials related to Jews from Afghanistan, Bukhara, Turkestan and Soviet Central Asia kept in the British Library (London) “Central Asia, Persia and Afghanistan, 1834-1922: From Silk Road to Soviet Rule.” (https://dbis.ur.de/SBBPK/resources/105217?lang=de)

Searching for, reading, and analysing articles related to the Jewish Triangle published in various European Jewish newspapers from the 19th to Mid-20th centuries. (https://sammlungen.ub.uni-frankfurt.de/cm) and (https://archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/search/archives/54a81142-600f-3ab9-b0a7-e3292f316879)

Research in Uzbekistan, 7-22 Nov 2023 (Thomas Loy):

Explorative work in the archives of the Samarkand State Museum (book holdings, photo archive, Lure collection) and preparation for further cooperation with this institution (processing of the previously uncatalogued holdings).

We met with scientists and representatives of the Uzbek Academy of Sciences (Tashkent), the General director of all Samarkand museums, the director of the fund and archive of the Samarkand State & RegionalMuseum, and scholars from the Bukhara State University to discuss about possible cooperation. Conducted first exploratory work in the National Archive of Uzbekistan. Gained access to the correspondences of Rakhamim Davidbaev with the Russian authorities in Turkestan to open the Bukharan Jewish newspaper Rakhamim (1909/1910).

Interviews in Samarkand, Bukhara and Tashkent with members of the Jewish communities, as well as with descendants of Jewish and Jewish-Muslim families who immigrated to Central Asia from Afghanistan and Iran (Mashhad).

With Zelimkhan Saidjonov, Asalshoh Khamraev (Bukhara State University) & Arkadi Issakharov (Tashkent)

With Zelimkhan Saidjonov, Asalshoh Khamraev (Bukhara State University) & Arkadi Issakharov (Tashkent)

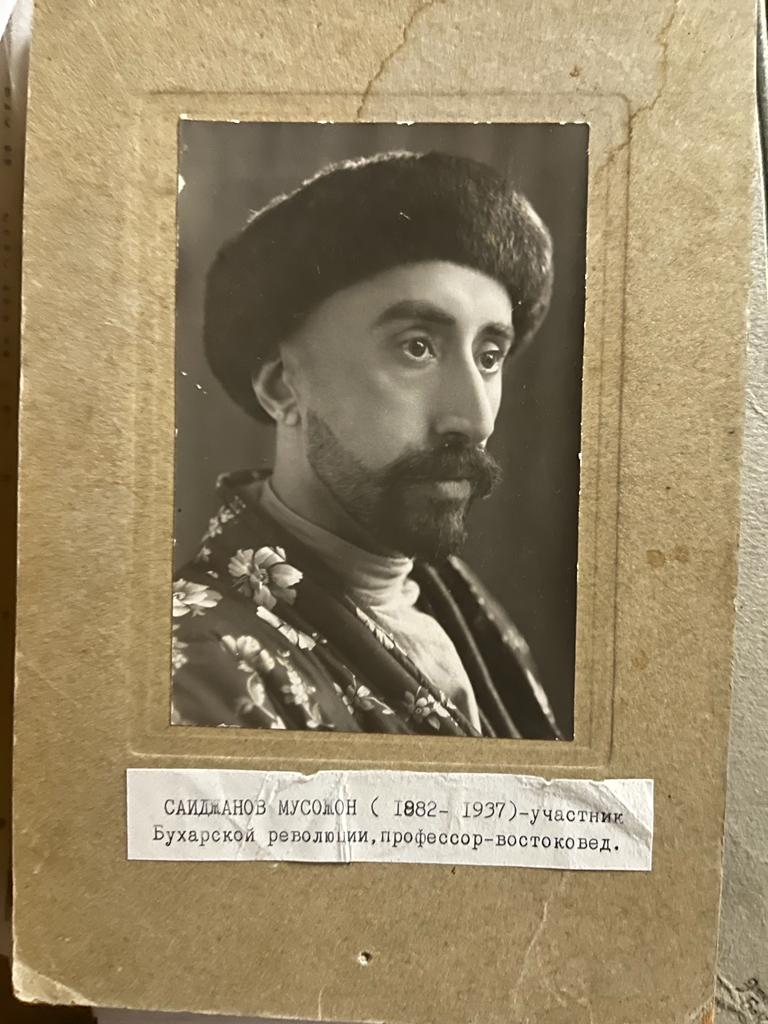

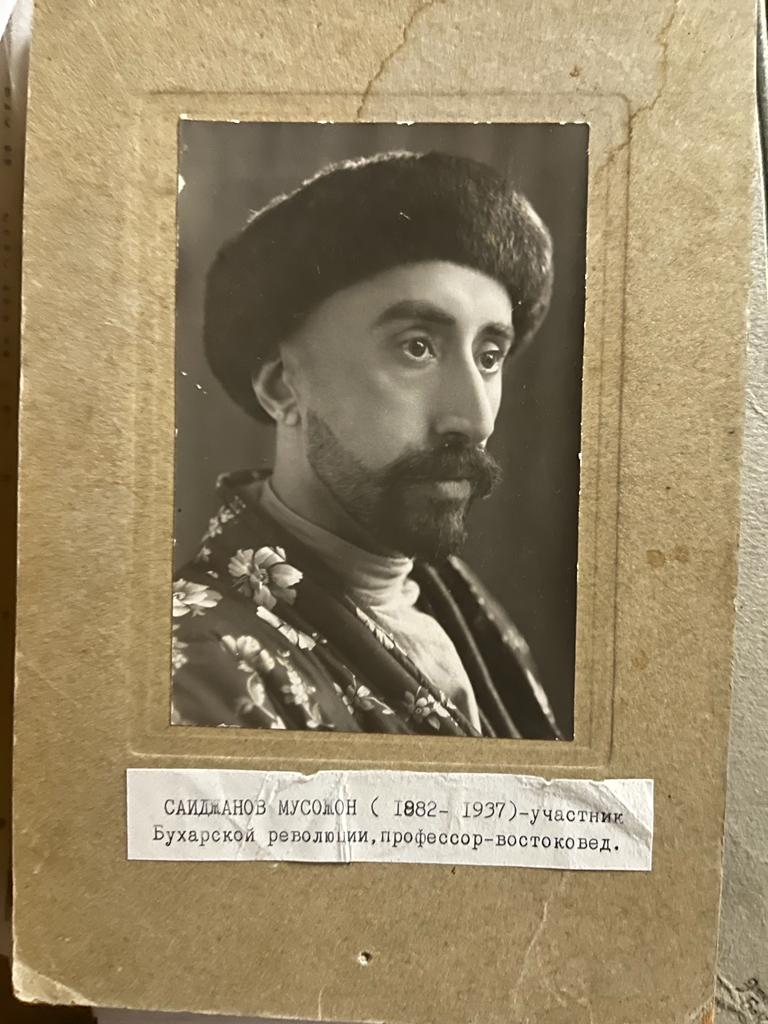

The fascinating family history told to us by Gauhar-apa and Selimkhan Saidjonov intertwines Jewish and Muslim trader families from Mashhad and Bukhara. Prominent personalities of this family history, who played an important role in Bukhara at the beginning of the 20th century, were the reformer, scientist, and politician Musojon Saidjonov (1893–1937) and the poet Payrav Sulaymoni (1899 –1933).

Portrait of Musojon Saidjonov. From Zelimkhan Saidjanov’s family album. Courtesy of Saidjanov family.

Portrait of Musojon Saidjonov. From Zelimkhan Saidjanov’s family album. Courtesy of Saidjanov family.

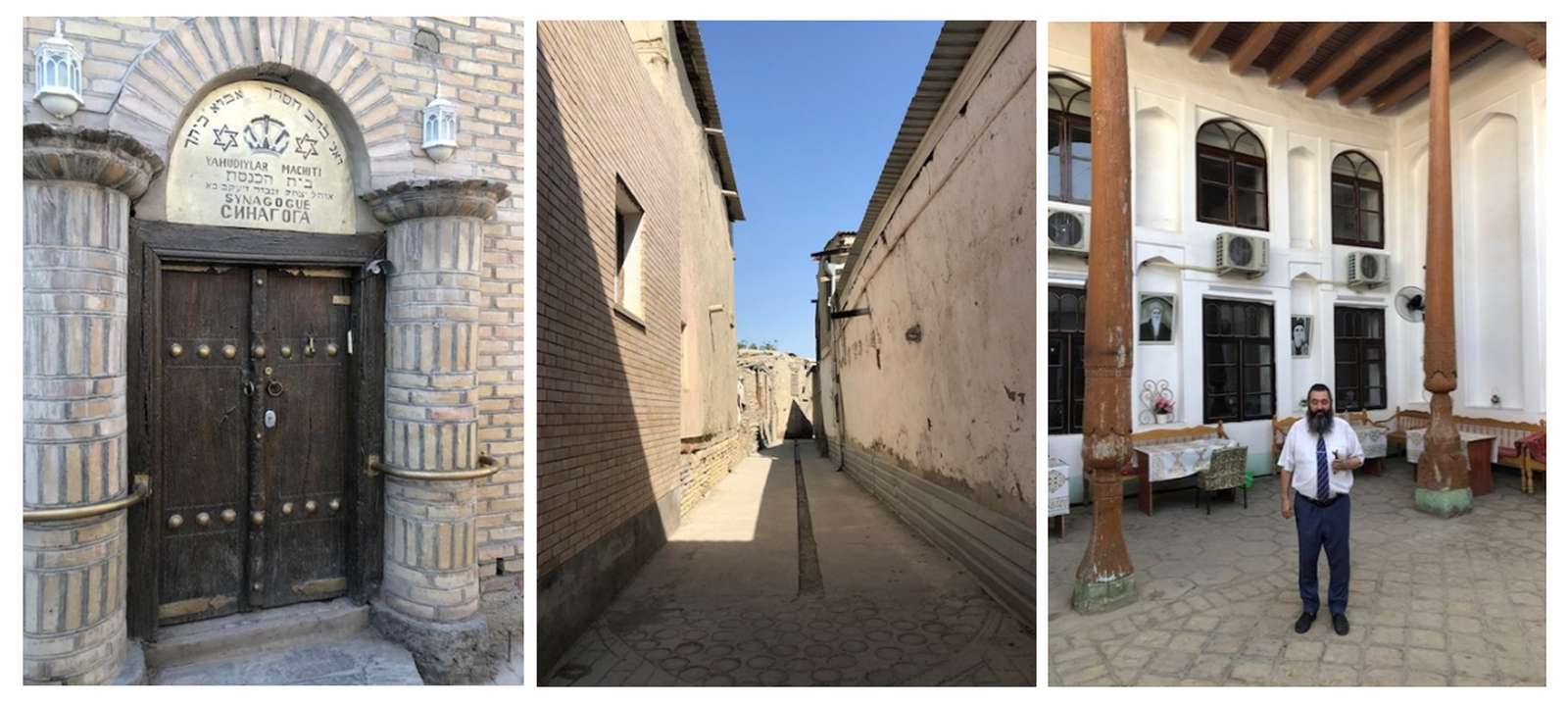

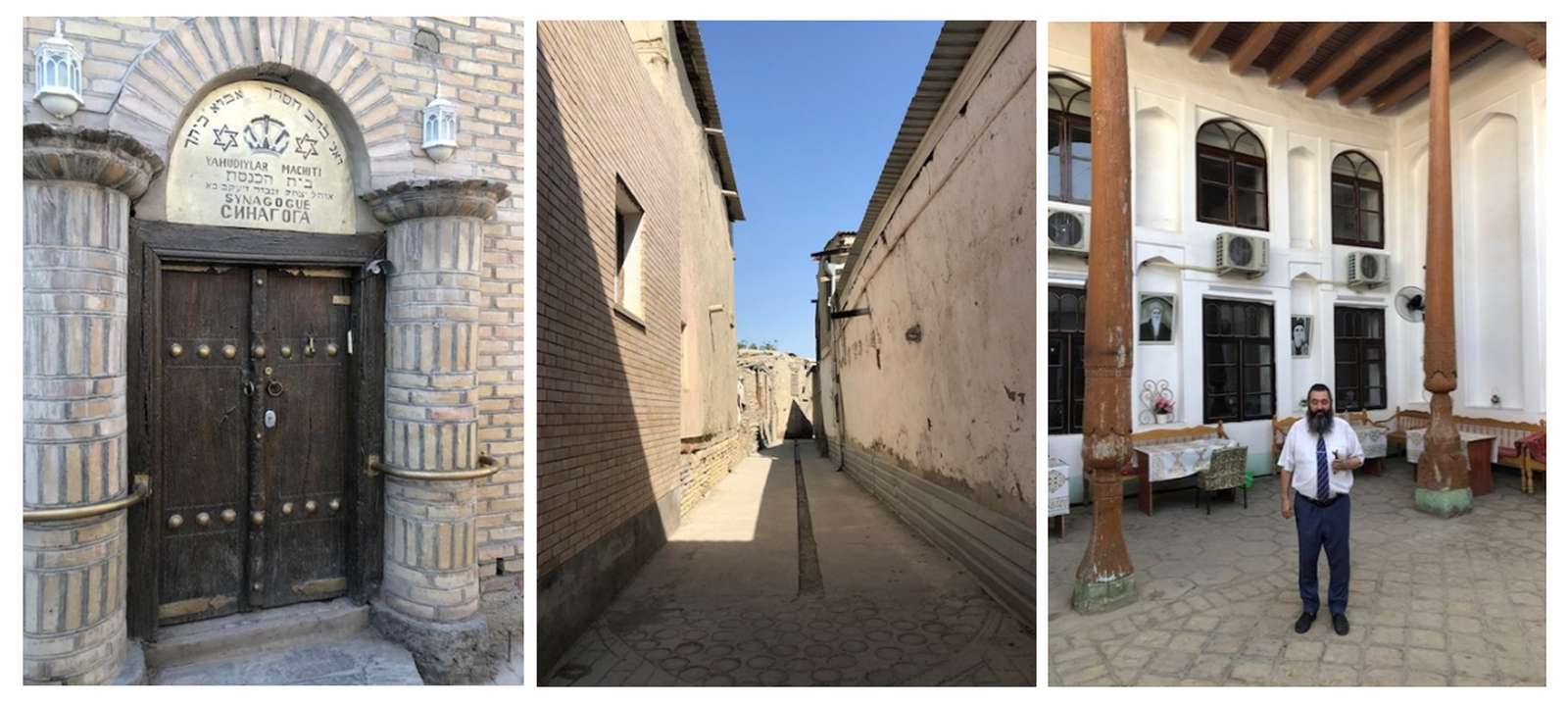

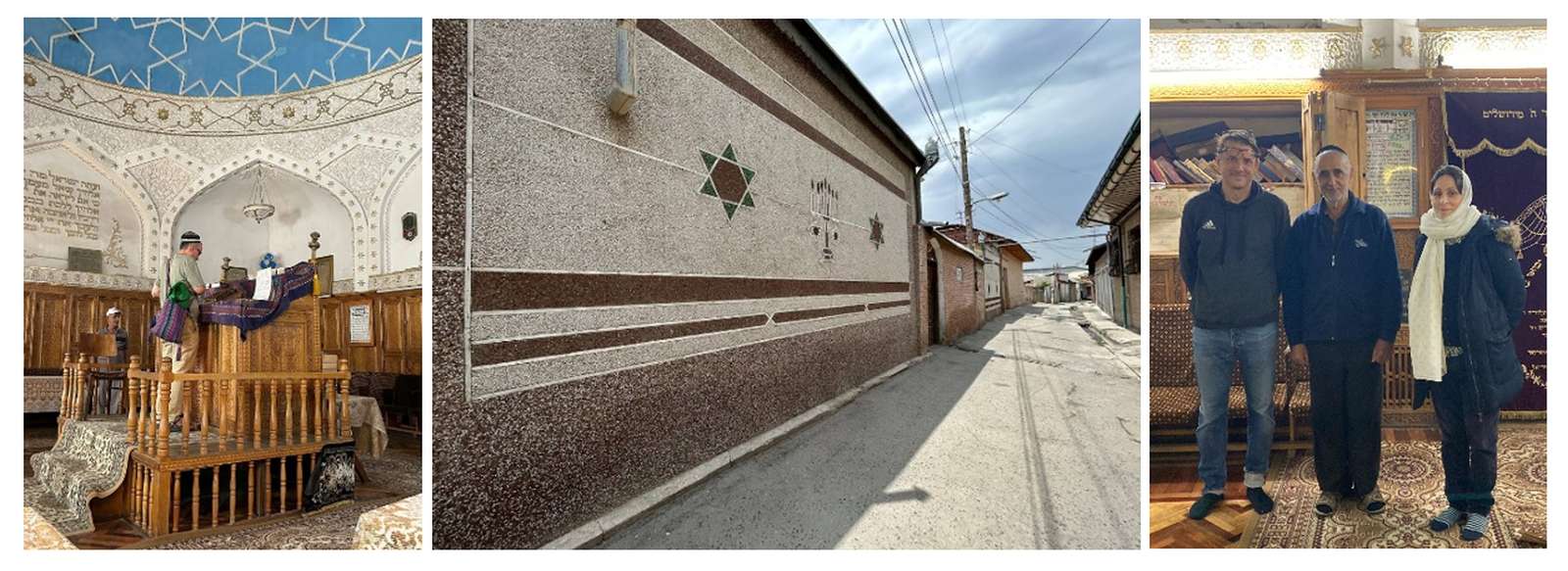

Meeting with Emanuel Elnatanov, the gatekeeper of the “second synagogue” in Bukhara.

In the early 20th century Bukhara had three Jewish neighborhoods (mahalai kuhna, amirobod, and mahalai nau) and eight synagogues (kaneso).

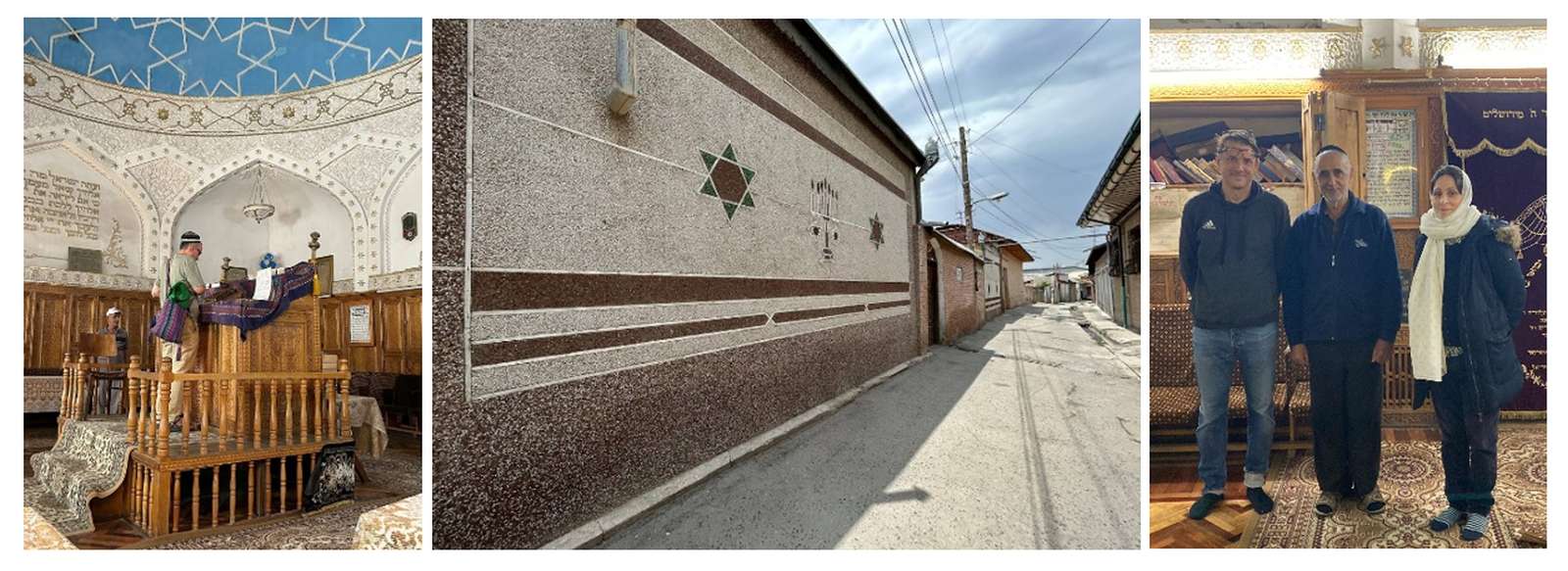

Visiting the Gumbaz Synagogue in Samarkand

Synagogue in Samarkand with Yakub-Aka and Dr. Ariane Sadjed. In the bookshelf behind us there are still some fifty old Hebrew prayer books (mostly printed in Vilnius and other Eastern European towns). The synagogue in the new town was closed for visitors because of the political tensions in Israel since November 2023.

Synagogue in Samarkand with Yakub-Aka and Dr. Ariane Sadjed. In the bookshelf behind us there are still some fifty old Hebrew prayer books (mostly printed in Vilnius and other Eastern European towns). The synagogue in the new town was closed for visitors because of the political tensions in Israel since November 2023.

You want to learn more about the Soviet period in the history of the Bukharan Jews? (https://reichert-verlag.de/de/fachgebiete/ethnologie_sozialwissenschaften/ethnologie_sozialwissenschaften_ethnologie_sozialwissenschaften_allgemein/9783954901845_bukharan_jews_in_the_soviet_union-detail)

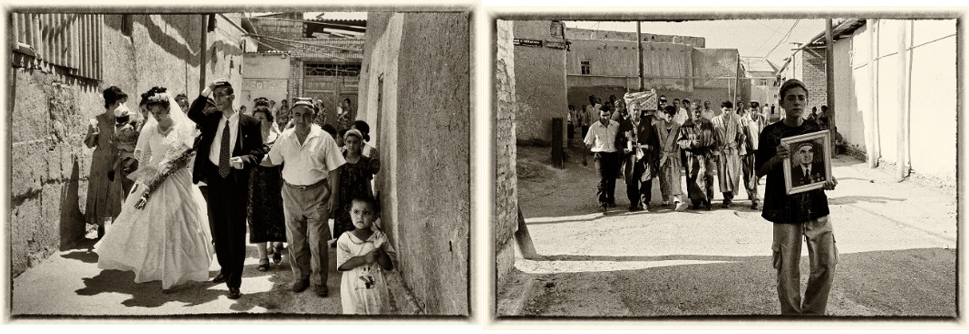

Explorative examination of the images of the Bukharan Jewish community in Bukhara taken by the photographer Shavqat Boltaev (died 2020) in the 1990s and 2000s.

Bukhara Wedding – Bukhara Funeral, Courtesy of Shavqat Boltaev.

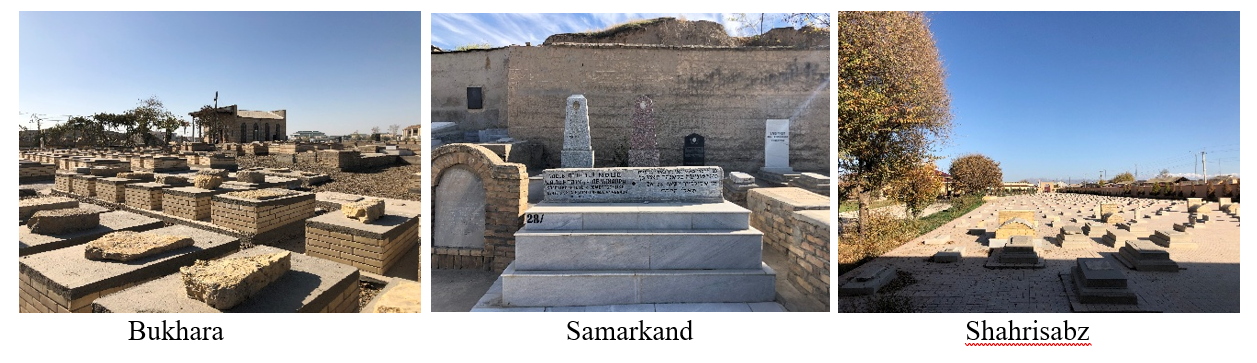

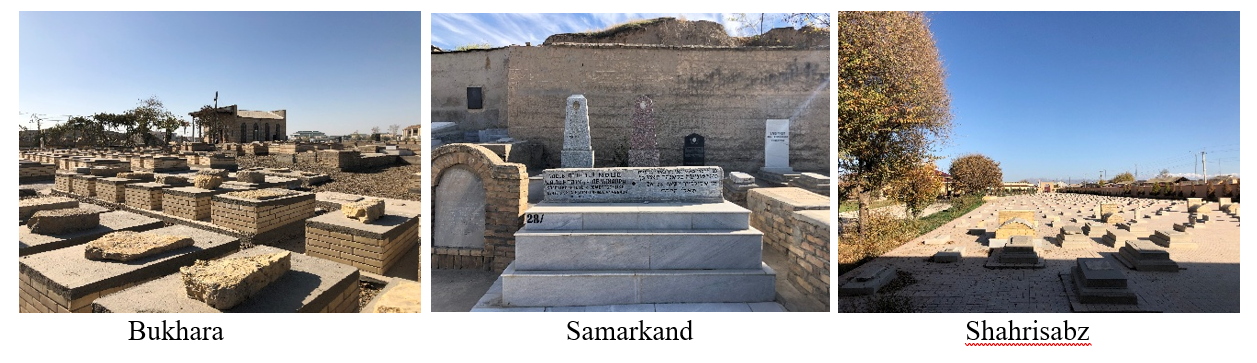

Visiting the Jewish cemeteries in Samarkand, Bukhara, and Shahrisabz.

In July 2024 we hired Dr. Ahmad Azizy for the project as post-doctoral researcher with a focus on the history of the Afghan Jews. From July to December 2024 Ahmad Azizy concentrated on sourcing relevant materials and compiling a comprehensive bibliography of Persian and Pashto-language literature and primary sources on the Afghan Jewry. His work included extensive research in newspapers, magazines, and published books originating from Afghanistan, focusing on Jewish life in the region.

On 11 July 2024, Thomas Loy was invited by Professor Magnus Marsden to participate in a roundtable event and an exhibition opening of the project: The Afterlives of Urban Muslim Asia (SOAS, London, Great Britain). The second panel at the roundtable event was chaired by Dawood Azami (Multi-Media Editor, BBC World Service). The speakers were Moska Najib (Afterlives project photographer), Thomas Loy (Oriental Institute, Czech Academy of Sciences and Afterlives Advisory Board member), Faisal Devji (University of Oxford) and Shah Mahmoud Hanifi (James Madison University and Afterlives Advisory Board Member).

Panel 2 with Faisal Devji, Shah Mahmoud Hanifi, Thomas Loy and Moska Najib (link: https://www.sussex.ac.uk/webteam/gateway/file.php?name=afterlives-newsletter-edition-3.pdf&site=11)

5-7 October 2024: Workshop in Prague: Jews in Central Asia & the Caucasus: Cross-Border and Power Relations in an Imperial Setting. Participants: Chen Bram (Jerusalem), Christoph Hopp (Potsdam, Haifa), Sara Rauchfuss (Berlin), Ahmad Azizy & Thomas Loy (Prague).

One result of the workshop was the agreement to start a joint translation and publication project. The aim of the project Translating Hebrew Scholarship on Central Asian Jewish History of the 19th and 20th Centuries is to translate important publications on the history and culture of the Jews in Central Asia and Afghanistan into English. The aim is to publish an English-language anthology by summer 2026 at the end of the GACR project. In this way, important works that were previously only available in Hebrew are made accessible to a wider readership and integrated into the academic discourse.

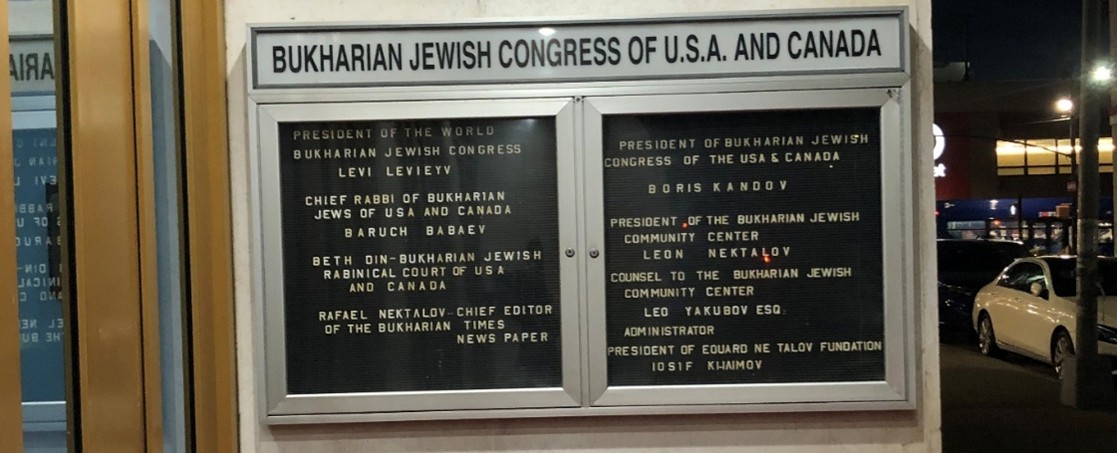

Research in New York, 3-23 November 2024 (Ahmad Azizy & Thomas Loy)

Due to the difficult and unpredictable political/security situation following the Hamas attack on Israeli settlements in October 2023 and the subsequent war in Gaza, we have decided to relocate the research work in the Bukharan and Afghan Jewish communities, initially planned in Israel, to the USA.

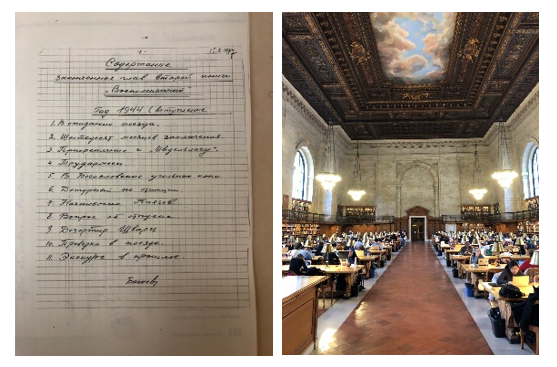

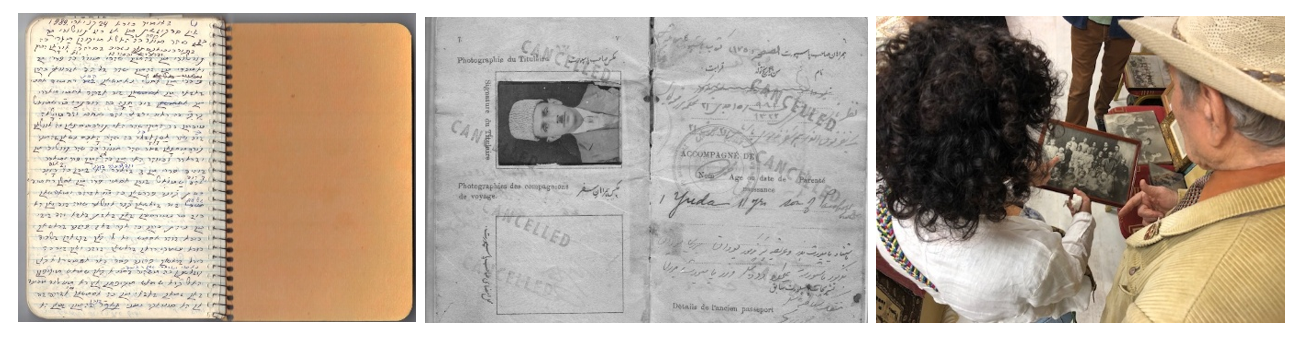

The primary objectives of this trip were to engage with individuals of Afghan-Jewish, Bukharan-Jewish and Mashhadi descents to understand their perspectives and historical experiences, as well as to locate and investigate archival materials (Bukharan Jewish Museum in Queens & NY Public library) related to the history of Jews in Central Asia, Afghanistan, and Iran. The trip proved highly productive, resulting in meaningful discussions, acquisition of grey literature, and the documentation of family-held historical records.

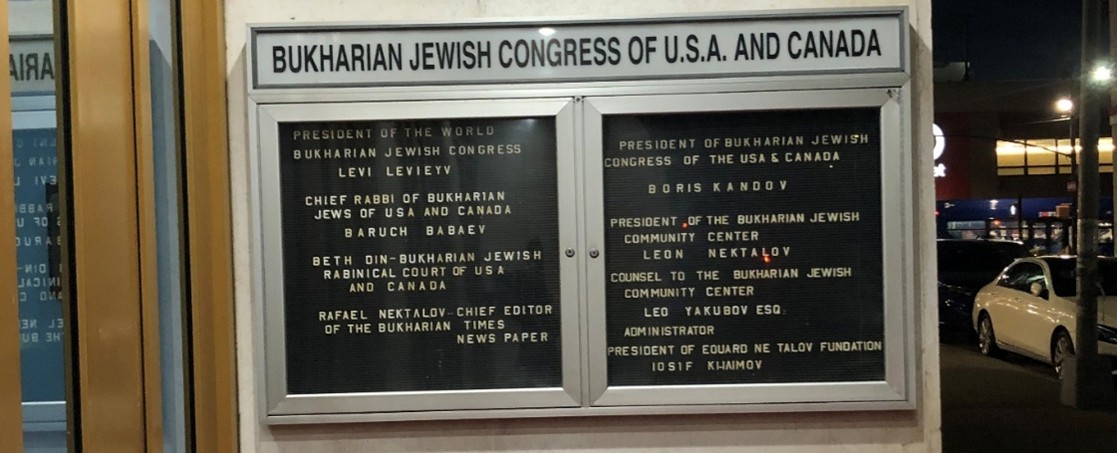

In New York we met with active members of the Bukharan and the Afghan Jewish communities. In addition to discussing the project’s research, opportunities for further collaborations were also explored.

Meetings with Abe Mor (Manhattan), Baruch Babaev (Chief Rabbi of the Bukharan Jewish Community) & Rafael Nektalov (The Bukharian Times) in the Bukharan Jewish Community Center in Forest Hills (https://www.bjccny.org/history), and with Aron Aronov and Alla Aronova (The Bukharan Jewish Museum), Roman Kaykov (Kaykov Media), and Robert Pinkhasov (President of the Klub Roshnoi) in Queens.

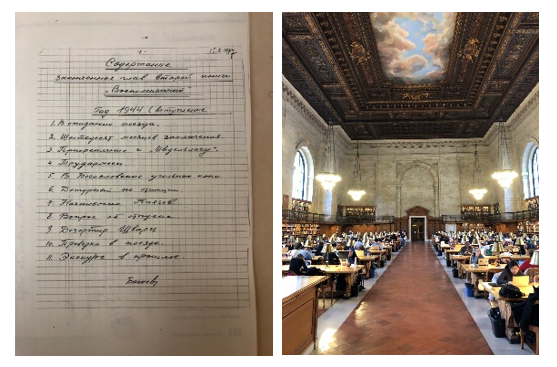

Document from the Edward Allworth Papers 1934-2011 (Box 6, 7, 10) kept in the New York Public Library. Included are copies of Mordekhay Bachaev’s manuscript of his memoirs: Yoddoshtho (Volume 1). Box 7 contains some transcripts of interviews with Bukharan Jews (conducted in Hebrew, partly in Israel in the late 1960s) – Parts of these transcripts were translated/summarized into English for Allworth.

Meeting with Osnat Gad in her Manhattan office, discussing the Herati past of her family and a planned exhibition of Afghan Jewish history.

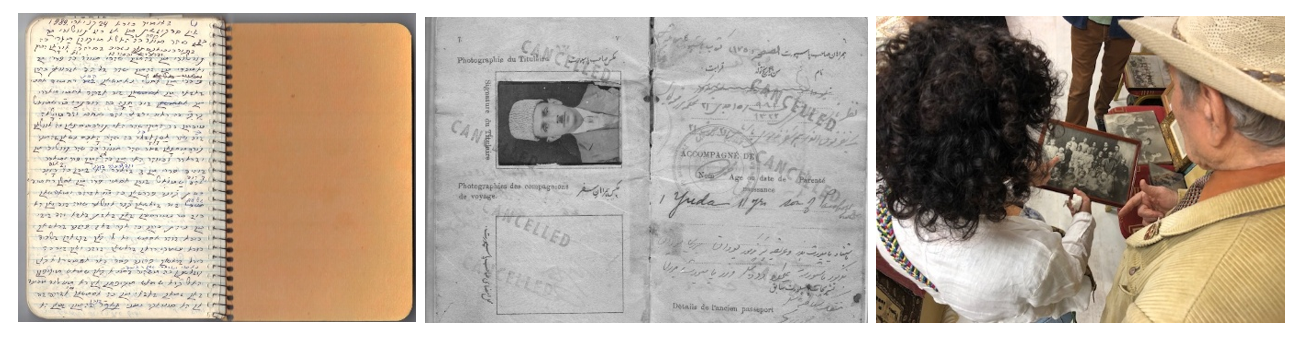

Thomas Loy is currently also working on the memoirs of Haim Abraham (1898-1997) and related archival materials, ego-documents, and secondary sources for an article on the Jewish history of Merv/Mary (in today’s Turkmenistan).

Haim Abraham’s Notebook & Haim’s passport. Dalia (Haim’s granddaughter) with a picture of her family taken in Marv in the early 1910s. She found it when we visited the Bukharan Jewish museum.

Haim Abraham’s Notebook & Haim’s passport. Dalia (Haim’s granddaughter) with a picture of her family taken in Marv in the early 1910s. She found it when we visited the Bukharan Jewish museum.

Founded in the 1880s, the Russian military garrison on the Trans-Caspian Railway quickly developed into a vibrant trade hub in the Transcaspian oblast’ and a town with a growing Jewish community consisting of Jews from Herat, Mashhad and Bukhara. Haim Aghajan Abraham was born in Marv in 1897. In the early 1910s, the Tsarist authorities forced the Jews to leave the city. Some returned to Herat (like Haim Abraham). Others moved on to Kerki, Samarkand, and other cities of Russian Turkestan.

The Bachaev family, Marv 1911. Courtesy of Lydia Bachaeva.

I was born in Marv. My father was what we call moshindūz [‘a machine-sewer’]. He was a tailor. What does a tailor want? He wants to make money. So he took his family and moved from Samarkand to Marv. He settled down there, opened up a tailor’s workshop and purchased a sewing-machine. At that time, sewing-machines were a novelty, the Russians would sell. These machines were driven either by hand or foot. I was born there in 1911. From an Interview with Mordekhay Bachaev (the newborn on the lap of his mother Avigail). Next to Avigail are Mordekhay’s sisters Bulur and Brukho. Mordekhay’s father Hiyo standing behind her. Mordekhay’s teenage brothers Juno and Hizkiyo standing next to each other. Their sister Esther with her son Ishay sitting left.

6-7 April 2025: Workshop in Prague: Connecting Jerusalem and Central Asia. Judeo Persian Printing and Publishing (19th/20th Centuries). (Invited guests: Dr. Zeev Levin, Ben Zvi Institute, Jerusalem; Christoph Hopp, Haifa & Potsdam University).

Thomas Loy contributes to an ongoing collaborative writing project on Jews in the Muslim World – for the chapter titled Connecting Jews/Displacing Jews (Diaspora and Networks beyond the Nation-State).

Between 1890 and 1914, Jerusalem was the exclusive center for Judeo-Persian printing and publishing. By the outbreak of World War I, more than 100 Judeo-Persian books had been published in the city and shipped and distributed to Jewish communities across Central Asia, Afghanistan, and Iran. These publications encompassed a wide range of genres, including Bible translations and commentaries, prayer books, rabbinical writings, religious philosophy, as well as Jewish-Persian poetry, historical narratives, dictionaries, and translations of secular works like One Thousand and One Nights, Abraham Mapu's first Hebrew novel Ahavat Zion (The Love of Zion, 1853), Shakespeare's Comedy of Errors. From 1910 to 1914, the Judeo-Persian newspaper Rakhamim was published in Russian Turkestan, marking the beginning of a thriving Judeo-Persian printing and publishing industry in Central Asia. In the 1930s, Judeo-Persian publishing (then called Judeo-Tajik and written in a modified Latin script) was strongly supported by the Soviet state before it was shut down by the authorities in the late 1930s.

This workshop aimed to explore the impact of Judeo-Persian printing and publishing in Jerusalem and Central Asia, localize these publications, and discuss their role in strengthening connections between Persian-speaking Jewish communities.

14 May 2025 Workshop in Prague Jews in Turkestan and Eastern Turkestan. Connections and Disruptions. (Invited guest: Dr. Michal Zelcer-Lavid, Bar-Ilan University; participants: Dr. Yu Miin-Ling, Inst of Modern History, Academia Sinica; Dr. Ondrej Klimeš, OI, Prague; Dr. Ahmad Azizy, OI, Prague; online participants: Gideon Elazar, Bar-Ilan University; Dr. Zeev Levin, Ben Zvi Inst, Jerusalem).

Persian-speaking Jews in Eastern Turkestan (modern-day Xinjiang, China) during the late 19th and early 20th centuries represent a little-known and under-researched chapter of Jewish history in Central Asia. European travelers and scholars documented small Jewish communities in cities such as Kashgar, Khotan, and Yarkand. These communities played a role in regional trade, serving as intermediaries between Central Asia, China, and South Asia. Eastern Turkestan can be considered one of the “unknown Jewish places” within the broader context of the “Jewish Triangle.” The fate of these communities after 1949, when Eastern Turkestan was incorporated into the People’s Republic of China, remains largely unknown. This workshop aimed to identify relevant sources and facilitate the exchange of knowledge about the Jewish presence in Eastern Turkestan and its historical connections to Jewish communities in Turkestan, Bukhara, Afghanistan, and beyond.

May/June 2025 Research in Israel and Workshop Herat – Mashhad – Merv: Jewish culture, history, and economy in the borderlands of Afghanistan, Central Asia, and Iran (19th and 20th Centuries) (29 May / in cooperation with the Ben Zvi Institute for the Studies of Jewish Communities in the East, Jerusalem). Participants: Zeev Levin, Yehoshua Ben-Zion, Ovir Haifry, Eti Amit, Chen Bram (Jerusalem), Ahmad Azizy, Thomas Loy + 2 guests.

This workshop explored the Jewish culture, history, and economy in the borderlands of Afghanistan, Central Asia, and Iran, with particular emphasis on the Jewish communities of Herat and Merv during the 19th and 20th centuries. By examining the interconnections between these often-overlooked communities, the workshop sought to illuminate their cross-border cultural and historical ties, which have received limited attention in existing scholarship. Bringing together scholars and community representatives, the event fostered discussions on the distinctive experiences of these Jewish populations and contributed to a deeper understanding of Jewish life in Central Asia. The workshop was held at the Ben-Zvi Institute in Jerusalem, in cooperation with the Oriental Institute of the Czech Academy of Sciences. One important result of the workshop was to link the Afghan community (Eti Amit) with the archive and documentation center at the Ben Zvi Institute. Materials about Afghan Judaism that cannot be published on the afghanim website (http://www.afghanim.co.il) will soon be reviewed, digitised and made available on the Ben-Zvi Institute documentary website (https://israelalbum.org.il/).

During our research stay, we visited the National Library of Israel (reading room for rare items) and the Bukharan Quarter (Shekhunat Ha-Bukharim) in Jerusalem. We were accompanied by Zeev Yekutiel and Eti Amit, who were both born and raised in this neighborhood in the 1950s and gave us a guided tour. We were also invited to Ramat Gan, where we met with members of the Afghan Jewish community at Hana Garji’s home. Some of the participants shared their childhood memories of Herat and/or Kabul. Most of them left Afghanistan in the 1950s. The meeting was recorded and will be published on the website www.afghanim.il Thomas Loy and Zeev Levin had a meeting with one of the leaders of the Jews from Turkmenistan (Efraim Yekutiel) in his house in Holon. We also met with Zilpo Cohen. She was born in 1946 in Herat and left Afghanistan with her family as a 12-year-old. She gave us some of her unpublished Hebrew autobiographical writings.

6-8 June 2025 Conference participation (Almaty, Kazakhstan): At the Crossroads of Cultures: The Jews of Central Asia and the Caucasus 2025 (Jewish Museum and Tolerance Center, Ben Zvi Institute, Turan University). Ahamd Azizy: Marginalization and Control: Afghan State Policies Towards Jewish Subjects in the First Half of the 20th Century // Thomas Loy (online): Reading Rakhamim — The Bukharan Jewish newspaper Rakhamim (1910–1914/16).

1-2 July 2025 Conference participation (Bonn, Germany, online): At THE FOURTH CESAI CONFERENCE OF AFGHAN STUDIES, we organised a panel on ‘Internal Strangers’ and ‘Border Crossers’ – Non-Muslim Communities in Modern Afghanistan. Panel participants: Ahmad Azizy, Riccardo Bonotto (EHESS, Paris), Thomas Loy, Magnus Marsden (University of Sussex). The panel was chaired by Professor Mikhail Pelevin (Saint Petersburg State University). Ahmad Azizy: Jewish Merchants and the Afghan State: Economic Control and Exclusion in the First Half of the 20th Century // Thomas Loy: Cross Border Identities: Herati Jews between Afghanistan, Central Asia, and Iran.

12-16 August 2025 Conference participation (Tashkent, Uzbekistan): We were invited to the THE TENTH BIENNIAL CONVENTION OF THE ASSOCIATION FOR THE STUDY OF PERSIANATE SOCIETIES (ASPS). In Panel 2.2.4—Jews in the Persianate World, Ahmad Azizy presented the paper: Marginalization and Control: Afghan State Policies Towards Jewish Subjects in the First Half of the 20th Century. Ahmad also read Thomas Loy’s paper: “Ba lafẓ-i fārsī” – Persian Language Use in the Bukharan Jewish Newspaper Rakhamim (1910-1914). The Panel was chaired by Houchang Chehabi (Boston University). During his stay in Uzbekistan, Ahmad also took the chance to visit the Jewish communities in Bukhara and Samarkand.

16-17 October 2025 International Conference in Istanbul: “Beyond Borders: Colonial Encounters & Challenges of Religious Minorities between Afghanistan, Central Asia, and Iran (19th–Early 20th Centuries)” .The conference was held in cooperation with and at the Orient Institut Istanbul and opened with a welcome speech by the institute’s director, Christoph Neumann. We had thirteen participants and presentations. Jonathan Lee’s keynote speech (“Sons of Adam, Members of the Same Body”: Identities and Survival Strategies of Non-Muslim Communities on the Borders of Empires) was open to the public and also streamed online. There were about 45 listeners on site and another 25 online.

Thomas Loy contributes to an ongoing collaborative writing project on Jews in the Muslim World – for the chapter titled Connecting Jews/Displacing Jews (Diaspora and Networks beyond the Nation-State).

Publications:

Thomas Loy

Article: The End of the ‘Jewish Triangle’. Geography and Mobility in Central Asia. In: Jewish Communities in Modern Asia. Their Rise, Demise and Resurgence. Ed. Rotem Kowner. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2023, pp. 25-46. (Book Chapter)

Abstract: This article introduces the concept of the Jewish Triangle as a lens to better understand the Jewish history of Afghanistan, Iran, and Central Asia.

Article: ‘Linguistic compatriots’: on the relationship between Tajik and Judeo-Tajik language and literature, Central Asian Survey, 44 (2) 2025, 202–224 (Published online: 03 Jun 2024) doi: 10.1080/02634937.2024.2342492

Abstract: This article follows the traces of Tajik and Judeo-Tajik literature in the early Soviet period and compares some prominent and some rather unknown works and biographies of Tajik and Bukharan Jewish writers.

Article: Redkollegiia. In: Literary Modernity in the Persophone Realm: A Reader. Eds. Christine Noelle-Karimi, Thomas Loy, Roxane Haag-Higuchi. Wien: Austrian Academy of Sciences Press 2024, 329–345. (Book Chapter)

Abstract: This chapter deals with the preface to the Almanac of Local Jewish Belles Lettres, an anthology of Bukharan Jewish poets and prose writers published in Tashkent in 1934. Next to short biographical accounts of the three editors of the Almanac (the so called Redkollegiia) the article provides a translation of the preface and a contextualisation of this first anthology of Judeo-Tajik Soviet literature.

Article: בלפזי פארסי / ba lafzi fārsi – The Bukharan Jewish Periodical Rakhamim and its Use of Persian (1910-1914)." Journal of Jewish Languages 13 (2025), 289–336 (published online 17 December 2025) doi:10.1163/22134638-bja10057

Abstract: This article examines the linguistic and historical significance of Rakhamim, a Bukharan Jewish newspaper published in Russian Turkestan from 1910 to 1914/1916. As an underused source, Rakhamim offers valuable insights into the linguistic development of Bukharan Jewish Persian and the history of Jews in Russian Turkestan.

Article (in print): Židovský trojúhelník – kontakty a přetrhané vazby v životě Židů ovlivněných perskou kulturou v 19. a 20. století (Novy Orient, issue 3, 77/2025 (in Czech)

Abstract: This article in Czech gives a short overview and outline of our current research project.

Article (forthcoming 2026) Ahmad Azizy and Thomas Loy: “The Herati Jews and the Afghan state: Mobility and Documentation Practices in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries.” The manuscript was submitted on 28 Nov 2025 to the editors of a thematic issue on Afghanistan in Iran & the Caucasus (Brill) and accepted for publication (with minor changes) on 12 January 2026.

Presentations:

Thomas Loy: Invited talk (11 January 2024, Philipps-Universität Marburg, Germany).

Title presentation: Jüdisches Zentralasien Die Bucharischen Juden im 19 und 20. Jhd.

Thomas Loy: Workshop participation (1-2 February 2024, FU Berlin, Germany): Borderland Capitalisms Reconsidered. Economic Practices and Contested Ressources in (Post) Imperial Siberia and Central Asia, 1822-1929. Title presentation: Haim Abraham: Borderland Encounters and Economic Practices of a Jewish Merchant between Afghanistan, Iran, and Central Asia.

Thomas Loy: Conference participation (7-9 June 2024, Georgian American University, Tbilisi, Georgia. In cooperation with the Jewish Museum Moscow and the Ben Zvi Institute Jerusalem): At the Crossroads of Cultures: The Jews of Central Asia and the Caucasus.

Title presentation: Jewish Merv – Colonial Encounters & Economic Practices between Afghanistan, Central Asia and Iran.

Thomas Loy: Invited talk – Roundtable event (11 July 2024, SOAS, London, Great Britain): The Afterlives of Urban Muslim Asia. Title presentation: Bukharan Jewish photographic heritage.

Ahmad Azizy and Thomas Loy: Organizing and conducting the Workshop (6-7 October 2024, Prague): Jews in Central Asia & the Caucasus. Cross Border and Power Relations in an Imperial Setting. Participants: Chen Bram (Jerusalem), Christoph Hopp (Berlin), Zeev Levin (on zoom, Jerusalem). One outcome is the additional publication project Translating Hebrew Scholarship on CA Jews.

Thomas Loy: Conference participation (7-11 January, CESS/ESCAS meeting, Lisbon, Portugal). Geopolitics, Migrations and Identities in Central Asia. (Panel: Adaptation and resilience: Jewish migrations to, from, and within Central Asia in the 20th Century) Title presentation: Mobility within – Bukharan Jewish migration in Central Asia (early 20th century).

Thomas Loy: Invited talk Afghanistan, Central Asia, Iran – “The Jewish triangle.” Oriental Institute Seminar Series, 8 April 2025, Prague.

Thomas Loy: Invited talk Old vs New? Mordekhay Muhib Bachaev (1911–2007) and Soviet Bukharan Jewish Literature (28–29 April 2025, online, Paris, France): “Progressivism for Souls? Literature and Spirituality in the (post-)Communist worlds.” Third Annual Workshop of the ‘RedGold’ ANR Programme.

Thomas Loy: Organizing and conducting the Workshop (6-7 April 2025, Prague): Connecting Jerusalem and Central Asia. Judeo-Persian Printing and Publishing (19/20th Centuries). Participants: Christoph Hopp (Potsdam, Haifa), Zeev Levin (Jerusalem).

Thomas Loy: Organizing and conducting the Workshop (14 May 2025, Prague): Jews in Eastern Turkestan. Connections and Disruptions. Participants: Michal Zalcer-Lavid (Bar Ilan University), Ondřej Klimeš, Ahmad Azizy (OI, Prague), YU Miin Ling (Academia Sinica), Gideon Elazar (online, Bar Ilan University), Zeev Levin (online Jerusalem).

Thomas Loy: Co-Organizing and conducting the Workshop (29 May 2025, Jerusalem) in cooperation with the Yad Ben Zvi Institute (Zeev Levin): Herat – Mashhad – Merv: Jewish culture, history, and economy in the borderlands of Afghanistan, Central Asia, and Iran (19th and 20th Centuries). Participants: Zeev Levin, Chen Bram, Ovir Haifry, Eti Amit, Yehoshua Ben-Zion (Jerusalem), Ahmad Azizy (Prague) + 2 guests. Title presentation (Ahmad Azizy): The Jews, the State, and Society in Afghanistan: Archival Narratives and Encounters // (Thomas Loy): Cross Border Family Histories – The Jewish Triangle and Beyond.

Ahmad Azizy & Thomas Loy: Conference participation (6-8 June 2025, online, Turan University Almaty, Kazakhstan, in cooperation with the Jewish Museum Moscow and the Ben Zvi Institute Jerusalem): At the Crossroads of Cultures: The Jews of Central Asia and the Caucasus. Title presentation (Ahmad Azizy): Marginalization and Control: Afghan State Policies Towards Jewish Subjects in the First Half of the 20th Century. // (Thomas Loy): Reading Rakhamim – The Bukharan Jewish Newspaper Rakhamim (1910–14/16).

Ahmad Azizy & Thomas Loy: Conference participation and panel presentation (1–2 July 2025, online, Bonn, Germany): The Fourth CESAI Conference of Afghan Studies. Panel title: ‘Internal Strangers’ and ‘Border Crossers’ – Non-Muslim Communities in Modern Afghanistan. Panel participants: Ahmad Azizy, Riccardo Bonotto (EHESS, Paris), Thomas Loy, Magnus Marsden (University of Sussex). The panel was chaired by Professor Mikhail Pelevin (Saint Petersburg State University). Title presentation (Ahmad Azizy): Jewish Merchants and the Afghan State: Economic Control and Exclusion in the First Half of the 20th Century // (Thomas Loy): Cross Border Identities: Herati Jews between Afghanistan, Central Asia, and Iran.

Ahmad Azizy & Thomas Loy: Conference participation (12–16 August 2025, Tashkent, Uzbekistan): The Tenth Biennial Convention of the Association for the Study of Persianate Societies (ASPS). Title presentation (Ahmad Azizy): Marginalization and Control: Afghan State Policies Towards Jewish Subjects in the First Half of the 20th Century. // (Thomas Loy): “Ba lafẓ-i fārsī” – Persian Language Use in the Bukharan Jewish Newspaper Rakhamim (1910-1914).

Ahmad Azizy & Thomas Loy: Conference organisation and participation (16–17 October 2025, Istanbul, Turkey): Beyond Borders: Colonial Encounters & Challenges of Religious Minorities between Afghanistan, Central Asia, and Iran (19th–Early 20th Centuries)

Title presentation (Ahmad Azizy): Trade, Taxation, and the Fall of the Ṣūm: A Jewish Petition from Tashqurghan to Amir Amanullah Khan, 1919 // (Thomas Loy): Cross Border Connectivity. Jewish Central Asia in the 19/20 centuries

Thomas Loy: Conference participation (18 December, online, Bukhara State University, Uzbekistan): Hozirgi Globallashuv Davrida Filologiyaning Dolzarb Masalalari [Current Issues of Philology in the era of Globalization] Title presentation: Die Sprache der Nachbarn. Judeo-Persisch/Tadschikisch. Sprache oder Dialekt? (in German)

Rakhamim (Mercy), title page, issue 1, May 1910

Rakhamim (Mercy), title page, issue 1, May 1910

With Zelimkhan Saidjonov, Asalshoh Khamraev (Bukhara State University) & Arkadi Issakharov (Tashkent)

With Zelimkhan Saidjonov, Asalshoh Khamraev (Bukhara State University) & Arkadi Issakharov (Tashkent)  Portrait of Musojon Saidjonov. From Zelimkhan Saidjanov’s family album. Courtesy of Saidjanov family.

Portrait of Musojon Saidjonov. From Zelimkhan Saidjanov’s family album. Courtesy of Saidjanov family.

Synagogue in Samarkand with Yakub-Aka and Dr. Ariane Sadjed. In the bookshelf behind us there are still some fifty old Hebrew prayer books (mostly printed in Vilnius and other Eastern European towns). The synagogue in the new town was closed for visitors because of the political tensions in Israel since November 2023.

Synagogue in Samarkand with Yakub-Aka and Dr. Ariane Sadjed. In the bookshelf behind us there are still some fifty old Hebrew prayer books (mostly printed in Vilnius and other Eastern European towns). The synagogue in the new town was closed for visitors because of the political tensions in Israel since November 2023.

Haim Abraham’s Notebook & Haim’s passport. Dalia (Haim’s granddaughter) with a picture of her family taken in Marv in the early 1910s. She found it when we visited the Bukharan Jewish museum.

Haim Abraham’s Notebook & Haim’s passport. Dalia (Haim’s granddaughter) with a picture of her family taken in Marv in the early 1910s. She found it when we visited the Bukharan Jewish museum.