The chapter presented here briefly summarizes the events and experiences of the Bachaev family in the city of Kokand in 1918. Mordekhai was six years old at the time. His father had relocated the entire family from Marv (in the Transcaspian oblast) to Kokand (the administrative and cultural center of the Ferghana oblast) two years earlier. After the Russian conquest in the late 1860s, the Ferghana Valley became the leading cotton producer for the Tsarist textile industry. In the mid-1910s, it was still Central Asia’s most thriving agricultural and economic region. Some of the Bukharan Jewish families living and trading in the Ferghana Valley (such as the Vaidiyaevs, the Simkhaevs, the Poteliakhovs, and the Davidovs) were among the wealthiest and highest-earning entrepreneurs in the Russian Empire.

After the October Revolution and the Bolshevik takeover of the province of Ferghana, local Muslim, Christian, and Jewish politicians and entrepreneurs made a joint attempt to establish an independent state on the territory of the former Kokand Khanate. The Kokand Autonomy was established at the end of November 1917. The Kokand autonomy was not recognized in Moscow, so the autonomists sought separation from Russia. It was not until early February of the following year that local Muslim fighters succeeded in taking control of Kokand’s old town, but without being able to capture the Russian garrison with the remaining Russian soldiers. Red Army troops and Armenian units, which had been brought in from other towns in the region, put down the “Muslim uprising,” resulting in heavy casualties among both fighters and civilians. By February 7, less than three months after its formation, the attempt to establish an independent state in Central Asia had failed.

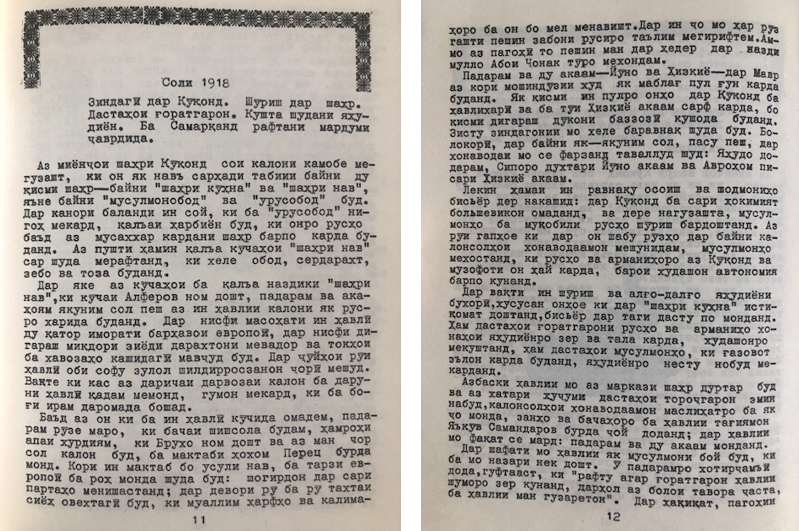

(Translated from: M. H. Bachaev, Dar Juvol-i Sangin, Vol. 1, Jerusalem 1988, pp. 11–16.

Reprint of the first edition in Muhib: Kulliyot, vol. III, Jerusalem: Tsur-Ot, 2006, pp. 11–16).

The Year 1918

A wide riverbed that typically carried little water ran through the city of Kokand. This riverbed formed a natural border between the city’s two parts, separating the old town from the new town, or “Muslimobod” from “Russobod.” On the high bank of this river, on the Russobod side, stood a large military fortress erected by the Russians after they took control of the city. Behind this fortress, the new town’s streets unfolded—lively, lined with trees, clean, and pleasing to the eye. In one of these streets, Alferov Lane, not far from the fortress, my father and older brothers had purchased a large courtyard from a Russian a year and a half earlier. Two rows of tall, European-style houses occupied one half of the courtyard, while the other half was filled with various fruit trees and grapevines trained on trellises. Cold, clear water flowed gently through the small ditches across the courtyard. When someone entered through the small door in the gate, they felt like they had stepped into the Garden of Iram.

One day, shortly after we moved into this courtyard, my father took me and my sister Brukho, four years older than me, to Hakham Perets’ school. I was six years old. The teaching in this school had been converted to a new method based on the European model. The students sat at tables, and opposite them, on the wall, hung a blackboard where the teacher wrote numbers, letters, and words with chalk. In this room, we had Russian lessons every afternoon. In the mornings, however, I attended Mullah Abo-i Jonak’s Heder and studied the Torah.

My father and two older brothers, Yuno and Hizkiyo, had saved considerable money from their machine sewing business in Marv. They used part of this money to buy the Kokand courtyard and fund Hizkiyo’s wedding. They invested the remaining amount in opening a small shop selling fabrics. Our lives were progressing well. Moreover, during that one and a half years, three children were born in our family: Yahudo, my little brother; Siporo, the daughter of my brother Yuno; and Avrohom, the son of Hizkiyo. But all these joys, peace, and success lasted only briefly.

The Bolsheviks came to power in Kokand, and it wasn’t long before the Muslims incited an uprising against the Russians. From what I could gather from the discussions among the adult family members during those days and nights, the Muslims intended to drive the Russians and Armenians out of Kokand and establish autonomy for themselves. During these disturbances, many Bukharan Jews, especially those living in the old town, were severely affected. Their homes were visited and plundered by marauding groups of Russians and Armenians, who killed many residents. Additionally, bands of Muslims declared a holy war, also killing many Jews.

Since our courtyard was located somewhat farther from the city center and there was a clear danger of being attacked by the looters, the family elders decided to move the women and children to the homestead of my maternal uncle, Yakub Samandarov. Only three men remained in our compound: my father and two older brothers. Next to our courtyard was that of a wealthy Muslim who had a good relationship with us. He reassured my father that if looters broke into our courtyard, we could simply jump over the wall into his courtyard. The following morning, armed looters knocked on our gate, shouting, “Hey, cursed Jew, open the gate immediately!” Our men remained silent and quickly slipped into the neighbor’s courtyard. From there, crouching, they watched the looters’ actions through a crack in the mud wall.

A band of thieves, consisting of about seven people, broke down the tiny entrance door of the large courtyard gate and quickly spread out across the entire courtyard. They forcefully broke open any locked house doors with the butts of their rifles. They rummaged through chests and cabinets inside the rooms, creating tremendous chaos. They packed valuable items into several bundles. If pillows were on the beds, they slashed them open with bayonets and scattered the feathers throughout the rooms. They also grabbed two fattened sheep, ducks, and chickens from the stables. Finally, they loaded everything they had gathered onto a cart and made off.

That same night, another group of looters visited my uncle’s courtyard. They shouted, “Put your hands up!” herding women and children, including me, into one room and the men into another. Then they began their search. Fortunately, Zulaykho, my uncle’s bride, escaped unnoticed through a hole in the wall when she saw the looters arriving. She ran to the city guards for help. Before the thieves could finish their misdeeds, they were warned by a whistle. Hearing this signal, they became anxious, abandoned their loot, and fled. Once they were gone, we learned that, at Zulaykho’s request, a mounted unit of the city guards had arrived and surrounded our courtyard. The looters’ accomplice, who had been watching outside and signaled them with his whistle, was arrested. We all, adults and children alike, felt very proud of Zulaykho and were grateful that we had escaped so lightly due to her attentiveness and bravery.

At the same time, the Muslim uprising intensified. More and more Muslims gathered from the villages around the city for the Holy War, armed primarily with hunting rifles and pistols. They brought Kokand carts loaded with cotton bales and positioned them near the riverbank. From this cover, they opened fire on the fortress.

However, as the saying goes, “One blow with an iron rod is worth more than a hundred needle pricks.” Massive reinforcements of weapons and new soldiers arrived from the city of Ferghana to support the Russian soldiers who barricaded themselves in the fortress. Suddenly, the Russians went on the offensive, unleashing a barrage of bullets from cannons and machine guns on the Muslims. When the insurgents fled, the mounted Russian units charged after them with cries of “Hurrah!” and finished them off. Those who survived scattered in all directions and went into hiding.

As a result of the cannon fire, many fires broke out in the city. The old town burned for days, and the flames consumed many courtyards and houses. The fire blazed so high that the adults could see it over our courtyard walls. To help me see, my older sister Bulur, who was perfectly beautiful, lifted me under my arms. When I witnessed the threatening fire, I feared it might reach our street and destroy our home. Noticing my fear, my sister said, “Don’t be afraid, my dear sister. Between us and the fire lies the river. The flames won’t reach our house.”

Due to the fighting and the fires, many people, including dozens of Bukharan Jewish families, lost their homes and all their possessions. The cold winter worsened their suffering. One day, my father’s cousin, Michael Putchaev, visited us. His courtyard was on the Muslimobod side. After the situation calmed somewhat, he went to check on his place. When he arrived, he found that all the wooden houses had burned down to ashes. He addressed my father, saying, “Dear Uncle, I am now homeless, and everything I owned has been destroyed. My only hope lies in the few gold coins I buried in two bowls under our house. If those bowls can be found, the money will alleviate my suffering. Otherwise, I am worse off than any beggar.”

My father tried to comfort his nephew, saying, “Don’t grieve too much! This misfortune has befallen many. At least you are physically unharmed—be thankful for that! I will accompany you with my two sons to search for these bowls. God willing, your money will be found again.”

When my father and brothers set out with a pickaxe and a shovel to Putchaev’s burned-down courtyard, I begged them to take me along. We walked for a while until we reached the other side of the river. Many burnt-out and destroyed buildings appeared before us. We arrived at Putchaev’s homestead and found that only a pile of rubble and ashes remained. Charred posts, beams, and rafters protruded from the debris in some areas, resembling a brittle skeleton.

The homeowner paused for a moment, looked carefully at the chaos, and then showed my father and brothers two spots where they should begin digging. The four men set to work with their pickaxes and shovels, removing ashes and wall remnants. With each shovel of dirt and ash, remnants of half-burned objects emerged: blankets, mattresses, carpets, and shards of porcelain dishes. Finally, they reached the floor. The homeowner continued digging beneath the foundation and successfully recovered the two bowls one after another. He quickly opened the lids and found the gold intact. Tears of joy filled his eyes, and with a broken voice, he said, “Thank God, now I am spared from begging.”

Due to bands of looters and gunfire from soldiers on both sides, many residents of the old town lost their lives or went missing. Among the victims were 85 Bukharan Jews, including Mullo Abo-i Jonak, the cantor of the Kokand synagogue, and my teacher. The Jewish community of Kokand gathered the bodies of those killed under the burnt and destroyed houses and took them to the Vadiyaev Synagogue for burial. They buried the victims in groups of five. Ovens and cooking areas were set up in the synagogue courtyard to bake bread and prepare meals, which were then distributed to the bereaved and destitute.

Quickly, news of death and destruction among the Kokand population spread to other cities in Turkestan inhabited by Jews. The leaders of the Jewish community in Samarkand took immediate action, appointing several people to send food and large quantities of clothing to Kokand by train to support the local Jewish community. These envoys stayed for a few days and distributed the items they had brought. With their advice and assistance, some of the plundered Jews were persuaded to leave Kokand and travelled by train to Samarkand. Our family was among those who fled from Kokand to Samarkand in 1918.