Haim Abraham’s Afghan Passports

Haim (Aghajan) Abraham was born in 1897 or 1898 in the city of Marv, located in the Transcaspian oblast of Russian Turkestan. Over the course of a remarkable life, he escaped Soviet Central Asia, built a trading empire from Kabul to East and South Asia, spent 25 years in Japan, and eventually passed away in New York in 1999. Though born under the Russian Empire, Haim Abraham was an Afghan citizen and carried Afghan passports – three of which have survived. This is the story behind them: How did Haim Abraham become an Afghan Jew?

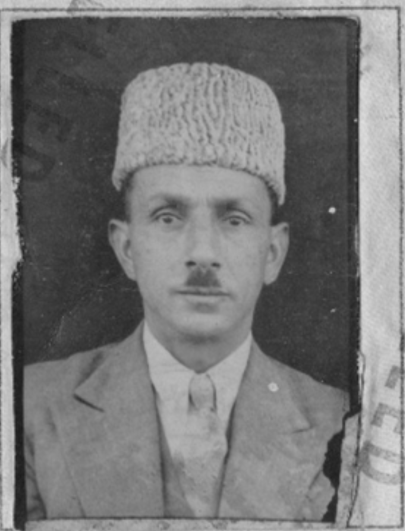

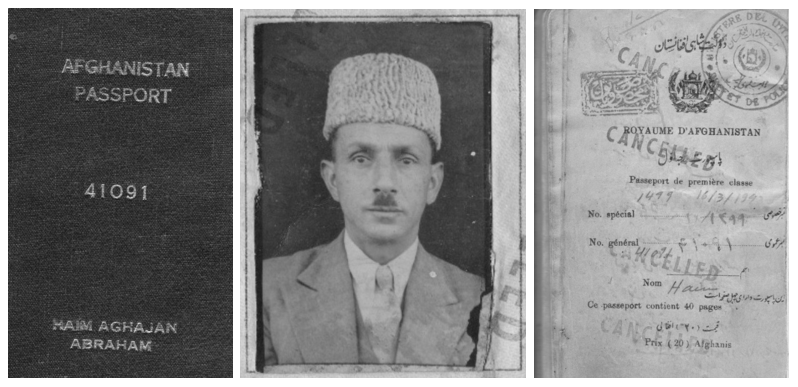

Passport Haim Abraham 1943, portrait Haim, page 1

Haim Abraham’s Afghan passport was issued in Kabul in 1943, initially valid for one year and renewed annually. The original passport had 40 pages, but over the next three decades, it grew – through countless renewals and visa entries – to over 200 pages. The passport was finally cancelled in 1974, with its last visa issued by the U.S. Consulate in Japan. On September 30, 1974, Abraham received a new passport from the Republic of Afghanistan. A decade later, despite Afghanistan's collapse into chaos following the 1978 coup and the 1979 Soviet invasion, he obtained yet another passport – this time from the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan. One year earlier, he had also acquired Israeli citizenship. In this way, Haim Abraham outlived both the Soviet Union and the Soviet-backed Afghan regime. Although he was born in Russian Turkestan, all of Haim’s Afghan passports list Herat in western Afghanistan as his birthplace.

The Herat Connection

Since the 1840s, Herat was home to the largest Jewish community in Afghanistan. Many of its Jews, including Haim’s father Aghajan Rakhamim, were merchants who travelled and traded across the region. After the Russian annexation of the Marv oasis in 1884, Aghajan left Herat and settled in the newly formed Transcaspian Oblast. Drawn by economic opportunities in the Russian-controlled territories east of the Caspian Sea, Jews from Afghanistan, Bukhara, and other parts of the empire settled along the expanding railway – especially in New Merv, which became a thriving trade hub linking Herat, Bukhara, and Samarkand.

In Marv, Aghajan married Hannah, the daughter of Shmuel Garji. The couple had nine children, with Haim being their second. The family remained in Marv for 25 years.

Marv, ca. 1890s, Unknown Russian photographer - public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5613498

The 1897 census recorded 8,500 residents in Marv and over 105,000 in the surrounding oasis – most of them Turkmen. Russian authorities categorized the region’s Persian-speaking Jews into three groups: Firstly, “local Jews,” who had lived there before Russian conquest and were granted Russian citizenship. Secondly, “Bukharan Jews,” who had migrated to Russian territory from the Emirate of Bukhara after the conquest and were considered subjects of the Bukharan Emir. The third category, to which Haim’s father and his children belonged – were “foreign Jews” who were treated either as subjects of Afghanistan or Persia.

After years of uncertainty and changing attitudes towards Jews in the Transcaspian oblast, the Russian authorities finally took action. In 1911, they expelled all Persian-speaking Jews from the border region with Afghanistan and Persia (including Marv). Except for the Mashhadi Jews, who were known as Jadid al-Islam and regarded by the Russian authorities as Muslims, all Jews had to leave. Most Afghan Jews went to Herat, others, for example, Haim Abraham’s family, resettled in cities with Jewish communities in Russian Turkestan.

Haim’s mother settled with the children in Samarkand. His father illegally stayed behind in Marv to protect family property. Haim later recalled that in 1912, during a visit to celebrate his Bar Mitzvah in Samarkand, his father was arrested and deported to Asterabad (modern-day Gorgan, Iran. Perhaps he simply fled there. Be that as it may, Abraham Haim’s notebook tells us that with the help of some Iranian (possibly Mashhadi) friends, the family sent some money to their exiled father, enabling him to obtain Iranian passports for himself and his family. Equipped with passports Haim’s father returned to Russian Turkestan, and settled in Marv again. These were likely the Abraham family’s first passports.

During the First World War, Central Asia’s political, economic, and security situation also heavily deteriorated. The year 1916 saw massive revolts all over Turkestan and a collapsing Empire. Two subsequent revolutions in St. Petersburg ended the rule of the Tsars and resulted in a civil war.

Escape from Soviet Central Asia

When the Bolsheviks took control and consolidated power in Central Asia, Abraham Haim was in his early 20s and still based in Samarkand. The communist regime confiscated private property and imposed strict travel restrictions. The Afghan consul in Samarkand intervened, issuing Haim and several Jewish families Afghan passports and facilitating compensation for their confiscated property. This is how Haim and his brothers got hold of an Afghan passport for the first time. These Afghan passports became their ticket out. During the early 1930s, as Stalin’s policies grew increasingly oppressive, thousands of Persian-speaking Jews fled Soviet Central Asia – Haim among them.

British diplomats noted that many Jews obtained Afghan or Persian documents by bribing Soviet border officials or consular staff, particularly in Tashkent. Until the early 1930s, cross-border marriages were one of the few options for Bukharan Jews to legally obtain an Afghan passport or a visa to leave the Soviet Union. Some men moved to Mazare Sharif, married local Jewish women, and settled. But this path also closed as Soviet-Afghan border controls tightened.

Already during the 1920s, Haim Abraham and his father expanded their business into Afghanistan, whose new ruler, Amanullah Khan (1919–1929), sought to modernize the country. Haim’s younger brother Hasid remained in the Uzbek SSR to continue the family business. After the Soviet government ended the New Economic Policy in 1929, private trading became nearly impossible. The introduction of the planned economy with its five-year plans considerably worsened living conditions in Soviet Central Asia. Many Persian-speaking Jews turned their backs on the Soviet state and fled. To avoid persecution in Soviet Central Asia, Haim Abraham took his wife and children from Kerki to Herat.

In 1932, Hasid married Dora Yagudaeva, a Bukharan Jew from Kokand (in the Ferghana Valley), whose father had been persecuted and perished in the Gulag. The young couple also prepared to leave. When accused of illegally trading diamonds, Hasid fled to Herat. His pregnant wife Dora was arrested and gave birth in prison. After six months, she was released and eventually smuggled across the border with their infant daughter Zina in 1933. The family reunited in Herat, a story retold in Dahlia Abraham-Klein’s Caravan of Hope – A Bukharan Woman’s Journey to Freedom.

A Global Trader with an Afghan Passport

In Kabul, the new Afghan government “nationalized” the lucrative Karakul business and facing a Soviet refugee crisis in Northern Afghanistan, they urged all Jews to leave the border region and return to either Herat or Balkh, move on to Kabul or leave the country. By the mid-1930s, when the Soviet Union finally closed and controlled its southern borders in Central Asia, the Abraham family had relocated from Herat to Kabul, which was emerging as the central hub for Jewish life in Afghanistan.

Looking for new trade opportunities, Haim obtained an Afghan passport in 1943, moved to Peshawar, and begun to expand his business network to British India and south Asia. The end of World War 2 opened new economic opportunities for Haim Abraham and his family. Haim’s brother Meyer made a fortune selling unused American military tires in Afghanistan. Haim settled in Bombay with his family, returning to Kabul only for business reasons.

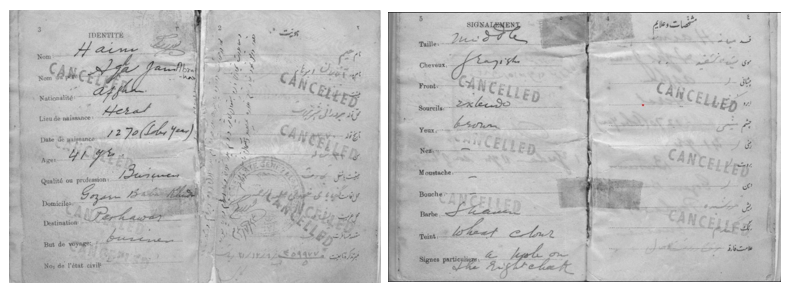

Passport Haim Abraham 1943, pages 2-5

The 1943 passport is bilingual (French and Persian) with handwritten entries in Persian and English. Later passports (see below) are printed in French and Pashto, which became the second official language in Afghanistan in the early 1930s. Nevertheless, the entries in all passports are still written in Persian.

The document listed his residence in Kabul’s Babayi Khudai neighbourhood. When I showed the passport to my former Persian teacher from Kabul, he said, “Thomas, that was my neighbourhood. I think I remember him – there was a Jewish family living nearby when I was a child.”

Haim’s portrait shows a well-dressed man in his forties, with a fine suit, karakul hat, and a prominent moustache. His physical description: medium height, greyish hair, wide eyebrows, brown eyes, shaved, wheat complexion, and a birthmark on his right cheek. His 11-year-old son Yehuda, Haim’s fourth child out of five, was also listed on the passport, but no other family members. His occupation: trader. His nationality: Afghan.

Passport Haim Abraham 1943, pages 6-7

In the 1940s and 50s, Haim expanded his trade network across South and East Asia (Bombay, Rangoon, Tokyo, Taipei, Hong Kong) and Europe (Milan, London), eventually reaching the U.S. He frequently visited Israel, and his passport includes visa stamps from across the world. With his Afghan passport, Haim Abraham became a global trader.

Enduring Change

During his first visit to Eretz Israel in 1947, Haim purchased land in Tel Aviv. In the 1950s and 60s, he travelled widely throughout Europe, Asia, and the U.S., where his son Mayer had lived since 1952. The Abraham family eventually built a global gem business, with offices in Hong Kong, Japan, India, and Thailand. In 1965, Haim relocated to Japan, where he and his sons Mayer and Yehuda opened offices in Tokyo and Kobe.

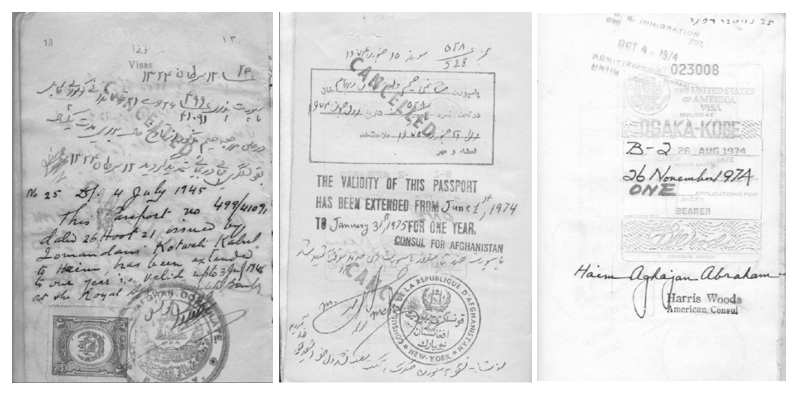

All extensions are stamped and dated by Afghan consulates, e.g., in Bombay (at the very beginning and again and again) but also very often in New York and once (12 January 1965) in Teheran. After obtaining the Afghan passport, Haim Abraham moved from Kabul to Peshawar (British India) and started an import/export business with Afghanistan. The last extension in this passport occurred in June 1974 – it was valid until 31 January 1975. The last visa for a trip to the United States was issued by the American consul in Osaka-Kobe in August 1974.

Passport Haim 1943, first extension (Bombay), final extension (NY), final visa (Osaka)

In 1975, Haim received a new passport after the previous one had grown too bulky. By then, the monarchy had fallen – President Daud Khan had overthrown his cousin Zahir Shah. The new head of state, who had served as a Prime Minister of Afghanistan from 1953 to 1963, turned Afghanistan into a Republic and became the country’s first President. But not for very long. In April 1978, the leftist People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan seized power in Kabul and killed Daud Khan and most of his family. This military coup d’état threw Afghanistan into upheaval and decades of conflict.

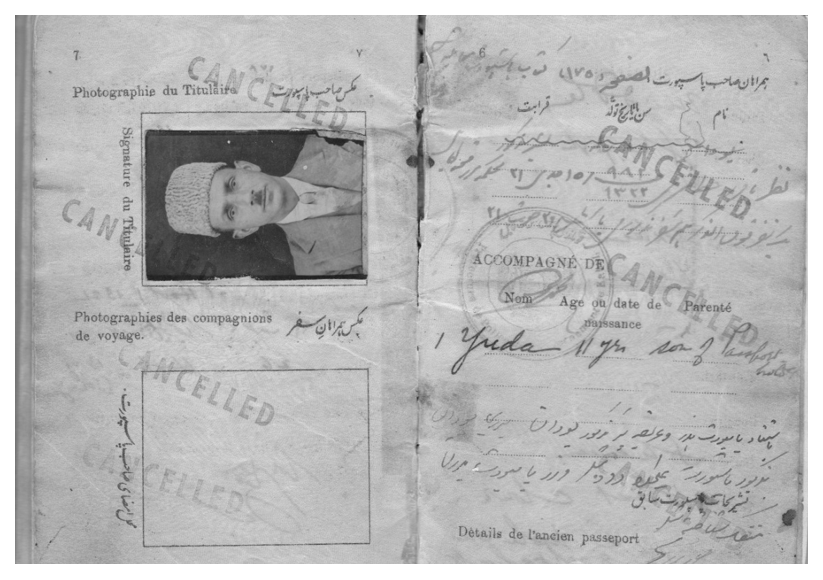

Passport Haim Abraham 1975, page 1, portrait Haim Abraham

Following the Soviet invasion in December 1979, Afghanistan changed yet again. The country that had issued Haim’s passport in 1975 no longer existed. In the early 1980s, he applied for a new document at the Afghan embassy in Tokyo. The Democratic Republic of Afghanistan issued him a new passport in October 1984, valid until 1987.

Passport Haim Abraham 1984, page 2

Interestingly, all three of Haim Abraham’s passports list different birth years – an unsurprising inconsistency. In 1897, there were no official birth certificates in Marv. In Soviet Central Asia, these were only introduced in the mid-1930s. In Afghanistan, they remain rare to this day. We rely, then, on Haim’s own recollection – born in 1897 or 1898 – not 20 June 1900 as indicated in his 1984 passport – while acknowledging that variations of a few years are to be expected. Some Jewish families recorded births in prayer books; others simply remembered.

All three passports belonging to Haim Aghajan Abraham are now in the possession of his family. My sincere thanks go to Dahlia Abraham-Klein for granting us access to these and allowing us to use them for our project work.

Thomas Loy (14 July 2025)